392. Environmental markets don’t emerge spontaneously

There are quite a few mechanisms that can be used to try to change people’s behaviour in order to generate environmental benefits. These days, the most rapidly growing approach seems to be the creation of new markets for environmental goods.

Historically, the main mechanisms used in environmental policies have been providing information, providing payments, imposing regulations, and creating improved technologies. All these are still used, but I’ve noticed that a lot of attention these days is being given to the use of markets.

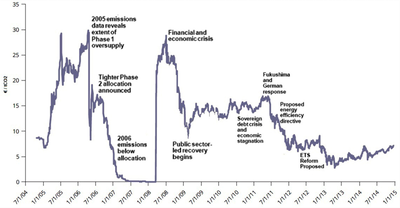

Examples of markets that relate to the environment include: the SO2 pollution market in the US (now defunct), various markets for permits to emit CO2, markets for biodiversity offsets, and the Reef Credits market in Queensland. The Australian Government is developing a market for biodiversity certificates, under its Nature Repair policy.

Examples of markets that relate to the environment include: the SO2 pollution market in the US (now defunct), various markets for permits to emit CO2, markets for biodiversity offsets, and the Reef Credits market in Queensland. The Australian Government is developing a market for biodiversity certificates, under its Nature Repair policy.

Economists generally love markets, as they are often an efficient way to manage things, but environmental markets have some differences from the types of markets usually talked about in economics textbooks. Notably, unlike, say, the markets for agricultural products like wheat or sheep, environmental markets don’t emerge spontaneously; they have to be created.

There are good reasons for that. When a farmer harvests a sack of wheat, it is clear who owns it – the farmer. When the farmer sells the wheat, it is clear to both the buyer and the seller what is being sold, and its quality can readily be determined by the buyer. The process of selling it is easy and cheap to do. No wonder wheat has been bought and sold in local markets for thousands of years.

How about a market for nature conservation? Could it emerge spontaneously, without a government (or some other institution) intentionally creating it? Clearly not. If somebody implements a conservation project, who owns the benefits? Nobody, and everybody, depending on how you think about it. We can all take pleasure in knowing that some conservation benefits have been generated. We don’t have to pay anyone to get that benefit, so why would we offer to pay? And what would a seller be selling, anyway? Intangible psychological benefits. Could a mythical buyer of these intangible benefits judge how good they are? Not easily. They probably don’t get to look at the conservation project directly, and even if they do, they probably don’t have the expertise to judge how good it is. And how would the transaction process work? Buyers would somehow need to locate sellers, negotiate the transaction and have money change hands. Given the other challenges outlined above, no system to facilitate and streamline this process has emerged spontaneously.

In economics jargon, environmental markets don’t emerge spontaneously because the property rights are not well-defined, and there are high transaction costs associated with obtaining high-quality information about the goods and conducting the transaction.

In creating a brand new market from scratch, these are key issues that have to be addressed.

Defining the property rights involves a few components. It is necessary to specify very clearly exactly what is being bought and sold. If you buy the good, exactly what do you get? Where is it? When can you get it? For how long will you own it? Can you sell it? How is your ownership of it assured and protected? What are all the benefits and constraints that go with owning it?

Demand for the rights to the good might already exist to some degree (e.g., a company might buy biodiversity credits as part of their corporate ESG strategy) or demand might need to be created or increased. For example, creating a regulation that says you cannot emit CO2 unless you own a permit that allows you to do so will create demand for permits.

To address the issue of transaction costs, a trading platform needs to be created to make it easy for buyers and sellers to connect and agree on a price. It needs to be backed up by reliable information about the prices in other transactions and about the amount and quality of the good. For environmental goods, having confidence in the information probably means having some independent process of measurement and quality assurance.

Recognising how much is involved in creating a market from scratch, it is actually quite remarkable that so many markets did emerge spontaneously. If you think about the markets that do exist, they all satisfy these requirements. If the requirements were not met easily or naturally, then somebody had to step in and make sure the requirements could be met. I recommend the report by the National Water Commission (2011) called “Water Markets in Australia: A Short History” for an excellent outline of how this was done in a particular example. One thing that stands out is that it wasn’t easy!

Recognising how much is involved in creating a market from scratch, it is actually quite remarkable that so many markets did emerge spontaneously. If you think about the markets that do exist, they all satisfy these requirements. If the requirements were not met easily or naturally, then somebody had to step in and make sure the requirements could be met. I recommend the report by the National Water Commission (2011) called “Water Markets in Australia: A Short History” for an excellent outline of how this was done in a particular example. One thing that stands out is that it wasn’t easy!

Further reading

National Water Commission (2011). Water Markets in Australia: A Short History Here