285 – The collapse of North Atlantic Cod

Humanity has a terrible track record when it comes to managing fisheries. There are many examples where over-fishing has led to the collapse of a fish population. One of the most spectacular collapses was the cod fishery in the north-west Atlantic.

Prior to the 1950s, cod had been fished off Canada for hundreds of years without any major decline in fish stocks. From the 1950s, fishing technologies improved and people got greedy.

“The decline began with the arrival of large factory stern trawlers in the late 1950s and the exploitation rate increased dramatically as these vessels were able to harvest cod offshore in winter months and at places where they were never previously caught,” (Grafton et al., 2009).

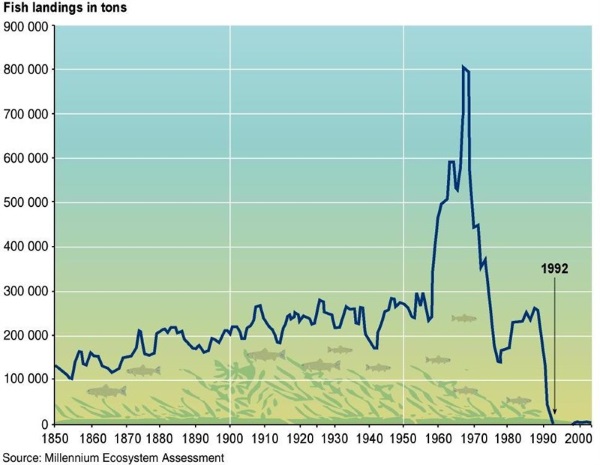

The numbers of cod caught by Canadian firms skyrocketed in the 1960s, crashed in the 1970s, recovered slightly in the 1980s and crashed to close to zero in the early 1990s.

The importance of the fishery to local economies in eastern Canada meant that their government was reluctant to take strong action to reduce fishing effort until it was too late. Right to the end, the government failed to respond as dramatically as it should have.

In 1992 they set a quota for cod catch that was more than the total amount caught the previous year. However, this quota was a foolish fantasy. By this stage the fish stock had been reduced to about one percent of what it was before the over-fishing started – there were almost no fish left that could practically be caught. So despite the quota, the government decided to impose a complete moratorium on cod fishing for two years, and since then the catch has been minimal compared to historic levels.

Ironically, the government’s delays in taking strong action were meant to benefit fishers, but this backfired terribly, resulting in huge job losses. The cod fishery had supported jobs for around 35,000 fishers and fish plant workers, although it should never have been that high, of course.

The dramatic reduction in fishing since 1992 has allowed cod stocks to recover a bit, but they remain very scarce compared to their earlier levels. In 2013 there were 10,500 tonnes of Atlantic Cod caught off eastern Canada, about 1% of the peak catch of 810,000 tonnes in 1968.

The loss of a dominant large fish from the marine ecosystem of the north-west Atlantic has had big flow-on effects, resulting in what ecologists call a “trophic cascade”, meaning that the populations of species lower down the food chain are dramatically altered.

We learn from our mistakes, if we’re sensible. In a few countries, fisheries management has improved significantly since the cod disaster. For example, New Zealand and Australia are relatively good at it compared to most countries. But globally, we are continuing to over-fish, to our own detriment. According to a 2008 report by the World Bank, “the difference between the potential and actual net economic benefits from marine fisheries is in the order of $50 billion per year – equivalent to more than half the value of the global seafood trade.” And “If fish stocks were rebuilt, the current marine catch could be achieved with approximately half of the current global fishing effort.”

We learn from our mistakes, if we’re sensible. In a few countries, fisheries management has improved significantly since the cod disaster. For example, New Zealand and Australia are relatively good at it compared to most countries. But globally, we are continuing to over-fish, to our own detriment. According to a 2008 report by the World Bank, “the difference between the potential and actual net economic benefits from marine fisheries is in the order of $50 billion per year – equivalent to more than half the value of the global seafood trade.” And “If fish stocks were rebuilt, the current marine catch could be achieved with approximately half of the current global fishing effort.”

Even in Australia there is more that we could do to secure our fish stocks in the long term. For example, Grafton et al. (2006) find that marine reserves where fishing is banned (Marine National Parks in our current parlance in Australia) can provide financial benefits to fishers in the long run, largely by accelerating the recovery of fish stocks in surrounding waters following an unexpected decline or “shock” (e.g. due to an environmental factor, or poor management).

If a Marine National Park is in place, fishers miss out on fishing in the reserve areas, but in the long run they are likely to be better off due to increased resilience, unless the frequency of shocks is really low.

Grafton et al. (2009) showed that a sizable no-take marine reserve in the north-west Atlantic (e.g. covering 40% of the total cod population) would have prevented the catastrophic crash in cod numbers, and would have been highly beneficial to fishers. However, the current review of zoning in our marine reserve system in Australia seems to be shaping up to reduce the planned area of Marine National Parks. I don’t think that would be in anybody’s interest.

Further reading

Grafton, R.Q., Kompas, T. and Van Ha, P. (2006). The Economic Payoffs from Marine Reserves: Resource Rents in a Stochastic Environment, The Economic Record 82(259), 469-480. Journal web site ♦ Ideas page

Grafton, R.Q., Kompas, T. and Van Ha, P. (2009). Cod today and none tomorrow: the economic value of a marine reserve, Land Economics 85(3), 454-469. Journal web site ♦ Ideas page

World Bank (2008). The Sunken Billions. The Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform. The World Bank. Washington D.C. Summary here

Very nicely done Dave, and an important message. Thanks for the references to our work too!

Interesting. I am now 77. I lived for the first 25 years of my life in the UK. The huge fishing fleets on north east coast of England and Scotland together with the fishing fleets from Iceland virtually eliminated cod and herring from the North Sea and beyond in the post WWII years, so 1950 and early 60s. As a boy, post war, I remember very big cod in the fishmongers (far bigger than the ‘salmon’ caught off the WA coast), cod was one of the staples of the famous ‘fish and chips’ and the Scottish kippers were big enough to fill a large dining plate. We should not forget haddock as the same fate nearly happened to them.

The dispute between Britain and Iceland nearly came to blows and the Royal Navy was dispatched to ‘protect’ the British fishing fleet from Icelandic gunboats.

Eventually everyone realised that the fishery had virtually been fished out and an agreement was reached between the countries.

In the eighties I was surprised that cod were available again. I remember I ordered one in a restaurant and when it arrived it was a little bigger than a modest trout.

The other interesting thing about fishing out fish stocks was the post WWII fish meal industry from South America. Fish meal was an important source of protein in our winter livestock rations, it was cheap too, compared to cotton meal, soy etc.,

I often wonder why we export canola as grain rather than oil and use the canola meal to develop a home grown protein source for our intensive livestock industries.

Sorry David wandered off topic there. It happens. Can I plug http://www.globalfarmer.com.au?

I will stand correction but i believe the fishery and so the catch is still controlled.

If you have the time this shows what i wrote about. It’s worth watching if you are interested in how easily we can deplete the oceans of their fish stocks. Don’t forget food rationing was still in force in the UK in the 50s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsOytZMRXo0

Thanks Roger. The program is more about the politics and the cod “war” than about the fish stocks themselves, but it’s still very interesting.

A scientific paper out last week shows northern cod have increased 100-fold since the collapse, and are now nearly recovered. Piece needs rewriting. Source: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/cjfas-2015-0346

In any case, generalizing to “North Atlantic” is wrong:Gulf of Maine is collapsed, northern cod nearly recovered, Iceland is fine, North Sea is recovering, Barents Sea at all time highs.

Thanks Trevor. The results in that paper provide very good news, and what great timing! My piece doesn’t need rewriting. There is only one point that needs correcting: where I say “they remain very scarce compared to their earlier levels”. That was true for a long time, but apparently no longer. I based my comment on the catch I indicated for 2013 (1% of the peak catch), which is the official number according to Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Perhaps that catch level in 2013 was determined by policy constraints rather than the availability of fish; I don’t know.

The lessons I identify still hold. The episode was disastrous for fishers and readily avoidable. It’s great that stocks have eventually recovered, but it’s taken 20 years, with a huge opportunity cost for all that time.

I think the article is sufficiently clear throughout that I’m talking about the fishery off Canada.

Sorry, I though that both the UK and Iceland mobilising their armed forces to protect their respective fishing fleets was a bit political.

Reminds me of the views that Australia should send its navy into the far south to protect the fish stocks against the factory ships.

My son forwarding the link to your very interesting paper Dave.

What a classic example of the limitations of politics. There are parallels that remind me strongly of the issues I am following in the management of a very different resource ~ Jarrah timber from Western Australia. The minimum size of a first grade Jarrah log is now down to 20cm diameter. And still we cut furiously. Where I live in Balingup there are currently two massive coupes nearby being harvested, both several square kilometers in area. One was previously logged in 1993, the other in 1997. Worst of all the resultant young Jarrah regrowth forest is unmanaged across thousands of square kilometers in the South West that are severly stressed without any dominant canopy emerging or any room for an understorey.

It was good to read Trevor’s update with regards to the slow recovery of the northern cod fisheries. In the Jarrah forests things are still getting worse every day presently, waiting for some politics of restoration to emerge. Or do we need to wait for forest collapse, just like for the cod?

Thanks Chrissy. Yes, the politics are pretty dispiriting.

David – you or Grafton probably know about this; I understand that the Norwegians have had a very different system for managing cod stocks from those used by the Canadians, involving much more local ownership (or at least control), especially in the areas where female cod go to breed, with the result that “their” stocks have not suffered the same decline.

Are there any international systems for managing fish populations that recognise that different stages of the life cycle might occur in different jurisdictions?

The links look interesting – thanks for the post.

Rob

Hi Rob

I knew nothing about Norwegian cod management. Went looking and found a few interesting things:

1. An article about how Norway and Russia run a Joint Fisheries Commission which sets harvest rules. http://e360.yale.edu/feature/how_norway_and_russia_made__a_cod_fishery_live_and_thrive/2806/

2. A booklet from the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs which explains their fisheries management system. It looks pretty impressive, at least at face value. https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/fkd/brosjyrer-og-veiledninger/folder.pdf

3. A 2013 presentation by someone from the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries. Also looks positive. http://www.naturoppsyn.no/attachment.ap?id=3260

None of these seem to cover local ownership or control. They don’t go into things at that depth.

Cheers

Dave

Anas Ghadouani sent me a link to this article in New Scientist, which also says that after a long period of very low numbers, the population has been significantly increasing recently, thanks to the prolonged ban on fishing. Good news.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27867-cod-make-a-comeback-thanks-to-strict-cuts-in-fishing/