284 – The world food price crisis of 2007

In 2007, the world prices for a number of important food commodities suddenly increased dramatically. Many reasons for the price hike were proposed at the time, but some of them turned out to have little to do with it. One factor that did play a big role was American policy that mandates use of biofuels.

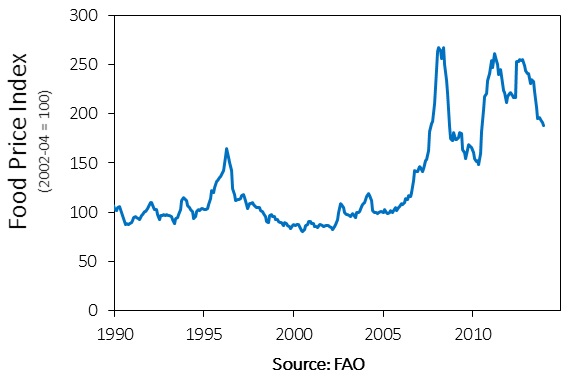

Between 2006 and 2008, the price of rice increased by around 200%, and the prices of maize, wheat and soybeans all increased by over 100%.

Figure 1. Index of food prices since 1990.

It was estimated that this big jump in food prices pushed an additional 130-155 million people into poverty. People rioted in protest at the high food prices in various countries, including Bangladesh, Mozambique, Egypt, Tunisia, Senegal, Zimbabwe and Haiti.

A number of possible reasons for the price rises were identified, including:

- Increasing oil and energy prices

- Drought and climate change

- Panic buying

- Export restrictions

- Increased demand for food in Asia

- Biofuel policies

It was felt at the time that it was the combination of all these things that did the damage. There were so many factors thought to have contributed that some described the situation as a “perfect storm”.

It was felt at the time that it was the combination of all these things that did the damage. There were so many factors thought to have contributed that some described the situation as a “perfect storm”.

However, we now have the benefit of hindsight and it’s clear that some of these factors played little or no role in the price spike (Wright 2014).

It’s true that the oil price spiked in the first half of 2007, just before the food price spike, so there is at least a smoking gun. Higher oil prices would have increased the cost of agricultural production to some degree, and this could have been passed on to buyers. However, Wright argued that this sequence of events (high oil prices followed by high food prices) was largely coincidence, not a causal link. He noted that prior to this event, there was no notable relationship between oil and food prices:

The 1970s oil spike began after the spike in grain prices was well under way, and another huge oil price surge starting in 1978 had no counterpart in the grain market. The sharp but forgotten spike in maize and wheat in 1996 was not matched by a similar movement in oil prices. When energy prices doubled after 1998, grain prices on average barely moved until 2006. (Wright 2014, p. 546).

If drought or adverse climate change was a significant cause, we would have seen significant declines in global food production in 2007-08. People observed that there was a big reduction in Australian grain production at just this time, due to the long drought in the Murray Darling Basin. However, Wright showed that there was no major decline in aggregate global production for any of the three major grains, so other countries must have had production increases that offset Australia’s shortfall. Furthermore, looking at past spikes in food prices, he found that (back to 1962) none of them coincided with large production shortfalls. This is intriguing, because a shortage should in theory cause a price increase, but it seems to have been overwhelmed by other factors in past years at least.

There was “panic buying” by several countries (Bangladesh, The Philippines, Nigeria and some Gulf countries) who increased stocks in an attempt to contain local food prices. This may have made a temporary contribution to higher prices on world markets, but it probably wasn’t a major factor. As evidence of that, I note that panic buying soon ceased, but prices remained high for several years (until about 2014).

A number of countries that traditionally have been exporters of cereal grains imposed a ban on exports during the crisis: Argentina, China, India, Egypt, Pakistan, Russia, Ukraine and Vietnam. This would have reduced the supply of grain in international markets. The World Trade Organisation and International Monetary Fund estimated that prices would have been 13% lower without these restrictions.

Increased demand for food in Asia, especially China, probably contributed. Higher incomes led to higher demand for meat, which led to higher demand for grain to feed to livestock, particularly soya beans. Higher prices for one grain flows through to other grains through substitution in demand. Wright noted that the evidence about the role of higher food demand in pushing up prices in 2007-08 is complex and somewhat confusing, but that it probably did play some role.

Finally, we have biofuels policy, particularly the US policy that caused large volumes of corn to be diverted away from food and livestock production and into the production of ethanol for use as a transport fuel. Although this was ignored by many commentators at the time, it undoubtedly played a significant role in the food price jumps. In addition to pushing up food prices, this policy increased the area and intensity of corn production, which probably led to increased environmental damage in the forms of water pollution, soil erosion and biodiversity loss. And, tragically, even in terms of its contribution to abatement of greenhouse gases, it was (and still is) a very poor policy. The climate benefits provided are small and very expensive.

One lesson from this is that we need to be careful in drawing conclusions about the reasons for changes in market prices. It is easy to be misled by simple correlations, such as that between 2007 oil prices and food prices. A plausible story is not sufficient evidence.

Another lesson is the importance of thinking through policies before committing to them. The failure to do that for biofuels policy in the US and Europe probably resulted in them doing more harm than good.

Further reading

Wright, B.D. (2014). Data at our fingertips, myths in our minds: recent grain price jumps as the ‘perfect storm’, Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 58, 538-553. Journal web site ♦ Ideas page for this paper

Quentin Grafton from the Australian National University sent me a recent paper by him and Hang To in which they investigate the impact of biofuel production and oil prices on food prices over the period 1981-2013. They agree with Brian Wright that biofuel policy had a big influence, but interestingly they disagree with him about oil prices, which they find to be even more influential than biofuel production. “… we demonstrate that both higher oil prices and increased biofuels production have raised food prices, and that this has contributed to global poverty and chronic undernourishment.” The difference may be because To and Grafton do a formal statistical model, whereas Wright’s conclusions are based on visual observations of the data. Sometimes a statistical model will find trends that are obscured because there are several changes going on at once. On the other hand, some of Wright’s observations are from before 1981. If these earlier years were included in To and Grafton’s model, perhaps the estimated influence of oil prices would be reduced.

To, H. and Grafton, Q. (2015). Oil prices, biofuels production and food security: past trends and future challenges, Food Security 7, 323-336.

A comment by Quentin (via email) on possible reason for the difference: “Wright fails to consider the ratchet effect associated with higher oil prices which accentuate the effects of biofuel subsidies. Basically, higher oil prices encourage production that would have gone into food to go into biofuels. At low oil prices no or very little substitution occurs, in the absence of subsidies or fuel mandates.”

I can appreciate the work done by Quentin Grafton and Hang To in comparison with Brian Wright’s submissions on the subject matter.

One takeaway for me is that both higher oil prices and increased biofuel production played significant roles in influencing food prices which contributed to global poverty and under nourishment within the period under observation.

A recent book that reinforces the message about biofuels:

The Economics of Biofuel Policies: Impacts on Price Volatility in Grain and Oilseed Markets

Harry de Gorter, Dusan Drabik, and David R. Just

ISBN 9781137414854

Publication Date April 2015

Publisher Palgrave Macmillan

The global food crises of 2008 and 2010 and the increased price volatility revolve around biofuels policies and their interaction with each other, farm policies and between countries. While a certain degree of research has been conducted on biofuel efficacy and logistics, there is currently no book on the market devoted to the economics of biofuel policies.

The Economics of Biofuel Policies focuses on the role of biofuel policies in creating turmoil in the world grains and oilseed markets since 2006. This new volume is the first to put together theory and empirical evidence of how biofuel policies created a link between crop (food grains and oilseeds) and biofuel (ethanol and biodiesel) prices. This combined with biofuel policies role in affecting the link between biofuels and energy (gasoline, diesel and crude oil) prices will form the basis to show how alternative US, EU, and Brazilian biofuel policies have immense impacts on the level and volatility of food grain and oilseed prices.

The price of P fertiliser jumped dramatically in 2008 – tripled /quadrupled. As cattle producers who apply P to pastures if the price hike had been maintained further we would have been forced to cease production as the price was too high for economic beef production.

Peak Phosphate is the elephant in the room for Australian and particularly Western Australian agriculture. Without P, farming in the south -west of WA would not be possible.

I have a video about peak phosphorus here:

https://youtu.be/AYgu1rEXPVQ

It’s tries to present a balanced picture on how serious (or otherwise) the threat of peak phosphosus is. It’s about 13 minutes long.

thanks David,

will watch this when I have time – in between writing a PhD, harvest, cattle sales, exhibition work etc.!

regards Nicole

I have witnessed this in today’s press brief here in Kenya maize price has risen and it is becoming unbearable for ordinary citizens to put a meal on the table.The government argues there’s enough maize in the cereal stores to feed the nation while the business people says it is of poor quality.

If biofuel caused large volumes of grains and cereals to be diverted away from food and livestock production and into the production of fuel and there is no change in fuel price, then biofuel policies should have been revised

Sorry Janvier but I don’t understand your comment. The point is that biofuel policy did influence prices.

I believe Janvier’s point’s assumption is that grain prices are affected by a) Fuel price (directly proportional) b) Grain supply (inversely proportional). Corn was diverted toward biofuel -which obviously diminished the grain supply, increasing the grain price as a result. But production of biofuel should have also decreased fuel prices (which i suppose was one of the objectives). The reduction in fuel price should have then balanced the surge in grain price as a result. This is not to dispute the argument that the biofuel policy had an effect on grain price. But I believe the policy had a sound logic but wrongly implemented. The decline in grain supply was far more than the decline in fuel price, leading to increase in grain prices.

I don’t think it would have reduced fuel prices. The increase in biofuels was achieved in the US by setting a minimum proportion of fuels that must be sourced from biofuels. If anything, that would push fuel prices up.

I cannot understand why it would “push fuel prices up” with the biofuel mandate in the US policy. Doesn’t the ethanol blend reduced the fossils demand, where in the US which mandates 10% ethanol blend representing 14 billion gallons a year, which would otherwise have added to the fossil fuel demand. If so, it may balance the price if not offsetting the fuel price here?

Fuel companies in countries without an ethanol mandate (or something similar) do not include ethanol in their fuel. The mandate constrains fuel suppliers in the US to include ethanol in the fuel that would not otherwise be there. Without the mandate, the cheapest fuel would not include that ethanol. By constraining fuel to require inclusion of ethanol, the overall price can only go up in that country. In other countries, the price of fuel would fall slightly, due to substituting ethanol for oil in the US, as the US demand for oil falls. (Ironic, given the “USA First” rhetoric coming from a certain quarter.)

Hi DAVID, sorry but I need some clarifications here, you mean that biofuel policies didn’t influence cause the rise of price in the global food crisis?

No, the opposite. They had an important influence.

The prices of the world major cereals also increased in Nigeria despite the panic buying as expressed in this article. We as country produce these cereal, however the production in still at a minimal stage in Nigeria especially wheat

Once again, policies must be thoroughly assessed before they are implemented. It is suggested in Ghana that, a political party lost 2008 election because of the 2007 food price crisis. David, I would like to know if (1) the price hike benefited the exporting countries and and impacted negatively on importing countries (2). Is there any global food policy that would ensure that food commodities are not diverted into the production of none food commodities which will result in food crisis? 3 . Can global food poisoning be suggested one of the causes of the price hike? I’m not familiar with any global food poisoning in around 2007 though. I’m sure you will help me if any.

1. Yes, sellers benefited and purchasers suffered.

2. The problem was a policy that actually encouraged diversion of crops from food to non-food. They just need to shut down that policy. They still need to do so. It’s a terrible policy, even from the narrow perspective of climate change abatement (which is what it is supposed to help with).

3. I don’t know anything about food poisoning. I haven’t previously heard of that as an issue.

The policy of diverting from food production in favor of production directed towards increasing animal production, does not only cause increase in global food prices, but also increases the chance of the population getting exposed to highly risky green house gases, like nitrous oxide and methane produced by ruminant animals through regurgitation process of chewing, animal products have got high content of protein, and excessive consumption leads of communicable diseases associated to obesity which becomes costly to treat, leading to high cost of living.

All in all, the policy is good but rather, it needs to balanced with an alternative that might counter the negative effect of the other hence inflicting less social economic burden to the population in the long run.

this post is very interesting and its seems like the rise in food was due so many reasons like drought and other factors and this affected the whole world very much and this problem was very serious and need to be solved as soon as possible. This post is really good and even I studied all the replies also and it looks like that all people around that world have different perception about this food price crisis.

With the factors leading to a price hike across the world in 2007, can we also say that the COVID -19 will trigger these factors? because countries are going to look withing first before they export. especially farmers may miss the planting season for next year’s production.

Precisely, note that COVID-19 also caused food hoarding globally so one should expect an automatic increase in food prices according to the Economic law of D & S.

Your lectures are easily understandable for me . That`s good, but there is only one thing that you have to be more attractive to the people who watches you. On the whole you the best lecturer i had ever seen. Thank you.

Thanks for your comments Arun. I agree – it would be good for the people who watch me if I was more attractive.

The economy in those countries was affected by the rise in prices and this fact shows the decline of the economy and the increase in poverty and scarcity since the 90s, such success was seen in that overwhelming increase in food prices worldwide , the issue of climate change is a factor that should not be excluded from the fact, since there are optimal production conditions so they will affect the results.

nice information

its interesting

Respected Professor Dr. Pannel, thank you for preparing this material and presenting it in a very understandable fashion. I belong to a one of the poorest land locked country where most of the people, about 65.5% of the total population, involves in farming but most of them are subsistence farmers. So, price hike has not affected to those 65.5% but every year there occurs a scarcity of the synthetic fertilizers followed by the flood and landslides and bad agricultural policy along with the lack of competing ability with the indian products, the prices are going up at this time.

Very nice contant delivered.

I think the foundational reason for the food price crisis was more demand Demand driven than supply related. The overarching reason for the hike in food prices was the high demand for grain and wheat. Like the rise in income which led to rice in demand for meat and subsequently rise in demand for animal feed, the policy on using wheat for biofuel was just one of the underlying factors for increased demand.

Sir you provide a lot of information

oil prices increased=biofuel production, which plays a significant role in producing a food crisis.

and yet: ” In the meantime, global biofuel production continued to grow, increasing 44% between 2011 and 2021.” Says:

IFPRI Blog : Issue Post

Food versus Fuel v2.0: Biofuel policies and the current food crisis

APRIL 11, 2023

BY JOSEPH GLAUBER AND CHARLOTTE HEBEBRAND

Yes, that’s true. To make matters worse, biofuels are not even a very efficient way to address climate change. When you consider the whole system, the cost per tonne of CO2 abated thanks to biofuels is extremely high. There are much better options available.