384. Biodiversity offset prices and biodiversity values

Increasingly, governments require developers to buy credits to offset any losses of biodiversity caused by their developments. In some cases, biodiversity offset credits can be traded in specially created markets. As a result of trade in these credits, we end up with a price being attached to biodiversity. Does that mean that, in some sense, the price of a credit represents the value of biodiversity?

I was asked this question recently by a colleague who was interested in whether credit prices could be used this way in an analysis he was doing. It would be convenient if they could, because information about offset prices is readily available. In short, the answer is no. Here is why. I’m going to set aside the various challenges in making an offset market work and just assume that it does work well.

Biodiversity offset credits are generated by landholders who do some actions on their land that protect or enhance biodiversity. The actions have to be things that they would not do in a business-as-usual situation – they are doing them in response to the opportunity to earn extra income from selling the credits. The government evaluates the actions and issues an appropriate number of credits. Doing the actions means that the landholders bear additional costs relative to business as usual, so they need to be compensated (paid) to be willing to undertake the actions.

Biodiversity offset credits are bought by developers because it is beneficial for them to do so. They can get a financial benefit because buying the required number of credits allows them to proceed with their economic developments, which make them money.

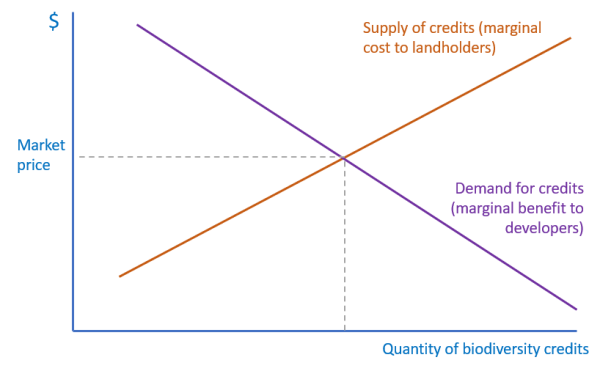

The price of credits in the market is then determined by two factors: the cost of generating credits (the supply side of the credit market) and the benefits of using credits (the demand side of the market). Assuming that the market is operating reasonably well (there are plenty of buyers and sellers, and there is a good system for connecting buyers and sellers and completing trades), then the price will be approximately where marginal cost equals marginal benefit or, in other words, where supply equals demand.

The marginal cost of generating a credit is the cost, at the margin, of generating an extra credit. Conceptually, imagine estimating the cost of providing every possible credit, ranking them from cheapest to most expensive, and then finding the cost that corresponds a particular quantity of credits. That is the marginal cost for that quantity. The higher the quantity, the higher the marginal cost.

For the marginal benefit, start by imagining there was only one credit available. It would get snapped up and used for the most profitable development, and that high profitability would represent the marginal benefit of that credit. As the availability of credits increased, they would get used for steadily less profitable developments, so the marginal benefit would fall.

At some quantity of credits, the marginal cost would equal the marginal benefit, and that would be the quantity of credits in the market (see the figure above). The price of those credits would equal the marginal cost and the marginal benefit at that quantity. Landholders won’t provide more credits than that because they cannot sell the extra credits at a price that would cover their costs.

Note that the price is not determined by the value of biodiversity to the community (which I’ll take to be the community’s willingness to pay to protect or enhance biodiversity). The value to the community depends on how much people care about protecting or enhancing biodiversity. In a normal market, how much they care is reflected in their willingness to pay for the good in the market, and so the market price gives us some information about value. (Market price is not the full story, even in this case. I’ll come back to that.)

In the market for biodiversity offset credits, the prices that buyers are willing to pay are not determined by how much the community cares about protecting or enhancing biodiversity. Instead, they are determined by how much money developers can make from their developments. There could be a big gap between the two.

Even for a normal market good, the market price alone doesn’t tell us the value of the good, except for the marginal unit of the good – the last unit consumed. For all the other units consumed, the marginal value is higher than the market price. To get the value of all the consumed units of a good, we need to know the shape of the marginal benefits curve, which we can use to estimate the “consumer surplus”, which is the overall benefit of consuming that good.

So clearly, the price of biodiversity credits doesn’t tell us this. It doesn’t even tell us the value of the marginal unit of biodiversity except in the extremely unlikely case where the current trajectory for biodiversity is the optimal trajectory. That’s because the explicit goal of an offset scheme is to maintain biodiversity on its existing trajectory. Even if the trajectory is declining, an offset scheme doesn’t fix that, it just stops it from getting any worse than it already would have done.

From that perspective, an offset scheme is not intended to help biodiversity at all. It’s intended to help development. The only exception to that would be if you think that in the absence of an offset scheme, the development would have been allowed to proceed anyway and the biodiversity would be lost. Compared to that scenario, having an offset scheme is better, but it’s clearly not a solution to our biodiversity-decline problems.

Interesting post, but I would want to add a further point and am curious whether you would agree with it.

At least some guides to CBA endorse using replacement costs, and the price of an offset is, I think, a type of replacement cost. This is because an offset is meant to fully compensate for the loss of biodiversity (whether this is the case in practice is a different question, but we are assuming that the offset market is working well). So, if a project has net benefits of $4 million without taking biodiversity into account and an offset for it costs $3 million, the project still has net benefits overall. Of course, you’re right to say that we don’t know the public’s WTP, but no one should be unhappy that biodiversity has been undervalued in this case because there is no net loss of biodiversity. On the flip side, it could be that the cost of the offset is higher than the value of the biodiversity at issue, because maybe the public would have preferred to have no offset and the $3 million (or even $2 million) spent on schools or returned to them through lower taxes.

Hi Rick

Interesting point. Yes, some guides do suggest the use of avoided cost or replacement cost as a way of estimating benefits that are otherwise hard to get at. My strong view is that this is not a valid approach unless the costs in question really would be borne in the without-project scenario. If the costs would be borne in the without-project scenario, then there is a simple financial benefit of the project from avoiding those costs. If the costs would not be borne in the without-project scenario, then they are irrelevant to any assessment of the project. Even if a replacement cost is included in the without-project scenario, it is in no way a valid measure of the value of the biodiversity itself. It’s a benefit because it indicates a cost saving, but the benefit is the cost saving, not the utility generated by the biodiversity.

So, as with many aspects of BCA, the key is to be totally clear about the with- and without-project scenarios. I give a couple of examples that highlight and explain the above issues in this video from my BCA course: https://youtu.be/JInLs5kD-h0

Cheers

Dave

Hi David,

I think this point is often optimistic:

” Instead, they are determined by how much money developers can make from their developments. ”

The developers doing the offsetting are, as you said, not doing this out of an environmental goal or need. Rather they are spending the minimum amount possible to meet the environmental standards required of them. That bare minimum won’t value the biodiversity nor the landholder’s efforts, so it is unlikely to meet the costs of the increased biodiversity (e.g. farmer labour is notoriously undervalued).

I think we all need to remember your point about offsets being something for the benefit of polluters, not farmers or the environment.

Thanks Dave for taking the time to reply. I see now that I didn’t properly explain what I meant – I wasn’t thinking in terms of costs that would be borne in the without-project scenario. I’m thinking that in the without-project scenario there is no construction cost (say to build a road), no benefits from a new road (ie travel time savings) and no project-related impact on biodiversity (no clearing and no offset). Then with the project there is a net benefit because the benefits from the new road exceed the construction cost and the biodiversity impacts net out to zero (because the negative clearing impact is cancelled out by the benefit from the offset). Anyway, don’t feel you should rely again, but I thought I should clarify.

Sorry, that last bit should have read ‘the benefits from the new road exceed the sum of the construction cost plus the offset cost, and the biodiversity impacts net out to zero’

Sorry, I was on the wrong track.

So, there is a question: do ‘the benefits from the new road exceed the sum of the construction cost plus the offset cost’? If they do, the developer will decide to proceed with the development and will bear the cost of the offset. If the combined costs are too high, the development won’t proceed. Whether this is the socially efficient outcome depends on the value the community places on the biodiversity that is being maintained. If the value of the biodiversity is less than the cost of the offset, then it may be that there is a net social loss due to the requirement for an offset. But if the biodiversity is worth at least as much as the cost of the offset, then the outcome will be efficient. Is that what you mean?

That’s it. So, instead of answering the question ‘Does that mean that, in some sense, the price of a credit represents the value of biodiversity?’ with ‘no’, I would say ‘in one sense, maybe’.

Hmm. Are you thinking about it in a revealed preference sort of way? Like, if the government chooses to require an offset, then they are revealing that they judge the value of the biodiversity to be at least as high as the cost of the offset?

No, I mean something much more limited. Without offsets you might not be able to say whether a project has net benefits because you have no dollar figure for the biodiversity loss from clearing. With a well-functioning offset market you can plug in the price for a suitable offset and if that results in a positive net benefit the problem is solved. To me that means that in one (limited) sense you could say that the price for an offset can represent the value of biodiversity (an upper bound value for inclusion in a CBA).

Maybe I’m being thick, but I’m not convinced. How do you know “if that results in a positive net benefit”? Doesn’t that imply that you know the value already? To me, it still seems that the cost of the offset just reflects the cost of getting the offset implemented, but not the resulting benefit (except in a loose, revealed preference sort of way as I mentioned before). What am I missing?

My argument relies on accepting that ecological experts can have the ability to judge the relative worth for biodiversity of different areas of native vegetation and biodiversity offsets. I don’t think such experts have any ability to value these things in absolute dollar terms, but I think it is plausible that they could do it in a relative sense. So they might say that clearing this area for a project will increase the probability of species X going extinct by 20%, but providing this offset will decrease the probability back to what it was without the project. In any case, this is usually the claim made for biodiversity offsets (no net loss). Of course, the experts need to understand all about additionality as well as about ecology. So you end up with net benefits = project benefits – project costs – cost of the offset – value of biodiversity loss from clearing + biodiversity value gain from the offset. You don’t know what the last 2 variables are, but you know they sum to about 0. It is certainly possible to disagree with all this because you don’t think experts can value biodiversity in a relative sense.

BTW I said above that the price for an offset could in one sense represent biodiversity value and I was just wrong about that, something I only realised from thinking about your comments, so thanks for setting me straight.

Thanks for persisting Rick. This has been a useful discussion.

I like your little equation: net benefits [of proceeding with the development project] = project benefits – project costs – cost of the offset – value of biodiversity loss from clearing + biodiversity value gain from the offset.

I agree that it is reasonable to hope that conservation scientists could judge whether the last two terms are about the same, in ecological terms. That is, after all, what they have to do when they evaluate what actions in an offset are required to deliver no net loss.

Glad we’ve reached agreement about whether or not the price of an offset in an offset market repesents the value of biodiversity.

I think a good way to look at the value here is to look elsewhere for a example as the value of biodiversity is massively misunderstood.

If you look at the example of building a hospital and the value then of that hospital they are very different things. It may cost $100million to build the hospital (think of that as replacement cost) yet the value to the community is hugely more than that (true value of the hospital).

If you cross this over to biodiversity the cost of creating the offset is simply the replacement cost and doesn’t represent the value of the biodiversity in any way. The value of biodiversity can only be calculated through by placing values on the ecosystem services provided, both the real (clean air, water etc) and abstract (value to amentiy, overall feelings of wellbeing, etc). In short offsets value a building/protection cost, not the value of the biodiversity within.

Exactly. Well put.