328. Weitzman discounting

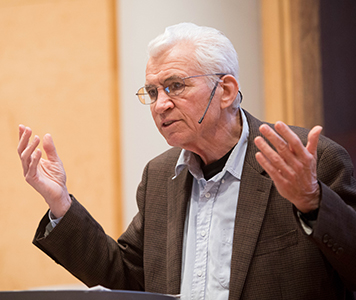

Martin Weitzman (1942-2019) was an environmental economist who thought laterally. He made important contributions to the field in at least three areas. Here I’ll explain one of his clever insights: that uncertainty about the discount rate has an impact on the effect of discounting.

At a function in his honour in 2018, Weitzman said “I’m drawn to things that are conceptually unclear, where it’s not clear how you want to make your way through this maze,” and described how he “took a decisive step in that direction a few decades ago…getting into the forefront rather than…following everything that went on.”

He certainly did get to the forefront! Like a number of other environmental economists I’ve spoken to, I was disappointed that he didn’t win the Nobel Prize in 2018 when his work on climate change and discounting would have made him a perfect co-winner with William Nordhaus.

This PD is about discounting. To follow it, you’ll need to know what discounting is, and how it works. For some simple background, see PD33, and for some insights as to why discounting values from the distant future raises curly questions, see PD34.

This PD is about discounting. To follow it, you’ll need to know what discounting is, and how it works. For some simple background, see PD33, and for some insights as to why discounting values from the distant future raises curly questions, see PD34.

You are probably aware that discounting at any rate likely to be recommended by an economist has the (perhaps uncomfortable) result that large benefits in the distant future count for little in the present. While there are arguments for accepting that this is in fact a reasonable and realistic result, it hasn’t stopped people looking for rationales to reduce the discount rate. Some really dodgy reasons have been proposed, including by economists (e.g. the Stern Report), but Weitzman came up with a simple idea that is obviously correct and has an effect equivalent to lowering the discount rate in the long run.

The insight was that, as we think about years further into the future, there is increasing uncertainty about what the discount rate should be in each year. This insight requires two breaks from the way that economists usually think about discount rates. The first is recognising that the appropriate discount rate to use is not necessarily constant over time. I remember thinking that it surely wasn’t constant when I first learnt about discounting, but then I just slipped into assuming that it is constant, like everybody else. Weitzman had the wit to remember that it didn’t have to be constant. [Technical note: I’m not talking about hyperbolic discounting here. In Weitzman’s conceptual model, the discount rate could go up or down from period to period.]

The second break from normal practice was to think about the discount rate for a given year as something that could be uncertain. It obviously is uncertain, but it had hardly ever been treated as such.

When economists want to represent uncertainty quantitatively, we usually do so by defining the value as a subjective probability distribution. To represent a discount rate about which we are increasingly uncertain in the more distant future, we would represent a probability distribution that has a wider variance as time passes.

Having done that, Weitzman showed that an uncertain discount rate is mathematically equivalent to a certain discount rate that declines over time. In the video below I show how this works.

The spreadsheet I use in the above video is available here.

The consequence, as described by Weitzman, is that ‘the ‘‘lowest possible’’ interest rate should be used for discounting the far-distant future part of any investment project’ (Weitzman 1998).

To get the declining-discount-rate result, you don’t even have to assume that uncertainty about the discount rate is increasing over time. As long as the rate is uncertain, even constant uncertainty will give that result.

The idea has been picked up in various ways, including in the guidelines for BCA published by the UK government. They don’t recommend doing all the uncertainty calculations explicitly, but they recommend using a discount rate that declines over time.

Note that to get the “lowest possible” discount rate, he really does mean “far-distant”. He’s talking about dates centuries into the future. The insight doesn’t have big implications for dates within about 50 years, which is about as far as many government Benefit: Cost Analyses go. For what I consider to be realistic representations of discount rate uncertainty, it would mainly affect the results for benefits and costs beyond 50 or 100 years in the future. (See the video for more on this.)

Note that uncertainty about discount rates in the distant future affects the impact of discounting in those distant future years. It doesn’t affect discounting in earlier years. As a result, even if the certainty-equivalent discount rate for year 100 falls to zero (i.e. the value discounted to year 99 is the same as in year 100), the values will still be discounted to express them as present values in year zero. So future benefits still get discounted quite a bit, just a bit less than they would have if you didn’t account for uncertainty. (See the video for more on this as well.)

Of course, the discount rate isn’t the only thing that gets more uncertain as we look further into the future – pretty much everything does. But Weitzman’s insight is still useful and relevant for some investments, even if you explicitly look at other types of uncertainty as well.

When would I suggest using Weitzman discounting? For a BCA that is capturing benefits and costs for 100 years of more. I would recommend combining it with strategies to represent uncertainty about other key variables in the analysis.

In other work, Weitzman focused on the possibility that the end result of climate change could be truly catastrophic. He called it a “fat tailed” problem, for reasons you can read about in Weitzman (2011) and Weitzman (2014). He concluded that this should “make economists less confident about climate change BCA and to make them adopt a more modest tone that befits less robust policy advice” (Weitzman 2011, p.291).

Further reading

Weitzman, M.L. (1998). Why the Far-Distant Future Should Be Discounted at Its Lowest Possible Rate, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 36, 201-208. Paper * IDEAS page

Weitzman, M.L. (2011). Fat-tailed uncertainty in the economics of catastrophic climate change, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 5(2), 275-292. Paper

Weitzman, M.L. (2014). Fat Tails and the Social Cost of Carbon, American Economic Review 104(5), 544-546. Paper

How would you apply discount rates to the activity of planting trees, where a key objective is to provide nesting hollows for endangered parrots, and the trees take 250 years to develop those hollows? I’m guessing a 7% discount rate would say it’s not worth doing, yet people do do it.

Yes, using a 7% deterministic discount rate, a value from 250 years in the future would be reduced by a factor of 22 million. I’d have to say I’ve never seen anybody actually do that, but if they did, that’s what they’d get.

This is a classic case where Weitzman discounting would be relevant. It would not remove the effect of discounting, but it would reduce it.

On the other hand, the issues I discuss in PD34 become relevant on that sort of time frame.

I first came across Weitzman in an article in the Economist reporting on his death last August. I suppose now he has died no chance of a Nobel.

Anyway thanks for the post and the copy of the live spreadsheet. I have not worked through it all but I find the argument intuitively very appealing and I take your quote from Weitzman to mean that perhaps we should not be discounting the benefits of climate change actions at all.

Which leads me to a possibly silly question: Is there any case for NEGATIVE discount rates? For example what if we really value the survival of the human species or, assuming no further or very low technological progress, we want to leave positive bequests for our offspring in terms of a resilient environment.

Yes, you have to be alive to win a Nobel prize.

I guess a negative discount rate is technically possible for a period. It would have some pretty uncomfortable implications though. e.g. that people in the present should bear costs in order to generate smaller benefits in the future. I see that there is some discussion of negative rates in various things on the web.

Thanks for helping us understand basic economics, David. The missing link for me now is why the discount rate is usually set positive. If money is put into a savings account of some sort, the interest rate is usually (in my experience) less than the rate of inflation. So the value of the money in terms of purchasing power, eg. CDs as you suggested somewhere, appears to be slightly higher now than after a year of investment. I’ve noticed from PD33 that inflation is factored out of discounting but this should be allowed for in the chosen discount rate (I may have garbled your words a bit). That seems to imply that the discount rate should be negative unless deflation is happening. Any tips or clues (for an environmental scientist) would be most welcome.

Good question. It’s true that current interest rates on deposits are less than the current CPI inflation rate. On the other hand, interest rates on debt are higher than the inflation rate. The latter is probably a better reflection of the opportunity cost of capital in the economy (the marginal rate of return on investment), so the appropriate real discount rate (net of inflation) would still be positive.

Current interest rates are generally very low relative to historic rates. When selecting a discount rate for future benefits and costs we have to make a judgment about future rates. If it is judged that the current low interest rates will not last, that would push up the discount rate used in a Benefit: Cost Analysis.

David, I am trying to send a reply but capture insists that 3+3 does not equal 6. Maybe this will get through:-

You’ve supplied the missing link for me, thankyou, David!

A topical case that may interest you in connection with discounting is the huge copper and gold mine being actively considered for the wilderness area at Pebble in Alasksa (Science 365, 6460, pp1367-1371 (2019)). The ore over the 20 yr life of the mine is said to be worth $300-500 billion. However, mines produce toxic leachates and sediment that might decimate a globally large salmon fishery worth $300 million per year. The fishery, properly managed, is sustainable indefinitely and requires relatively little new capital investment. Furthermore, the value of fish increases with inflation, whereas the mine leaves a legacy of clean-up costs. The choice of discount rates to apply to each project, especially pre- and post-mining, could be stimulating to think about. Nice little project for someone in the dept perhaps??

No reply needed.

All the best, John

Yes! We know capital goods render services now and in the future. The current price of a capital good is the sum of current services and the present value of expected services. Let us be clear. The cost of borrowing is not the sum of the interest payment, but is instead the present value (discounted values) of the future interest payment, even with zero inflation (a heroic assumption) earlier payments are greater sacrifices of consumption potential than are later payments of the same dollar amounts. The market value of wealth. One is perplexed as to how an environmental or agricultural economist is different to an economist? Economic theory is applicable regardless of circumstances (Soviets, Sweden, prisoners of war camps, market economies, etc.). There is no universal standardised definition for profit. Authors should define before just presenting. Some theoreticians explain profit as any increase in wealth in excess of that implied by the expected rate of interest. Before signing off on a seven percent interest rate (discount) it would be helpful to explain the real rate of interest plus inflationary expectations. Bottom line – a little too eclectic. More explanatory theory required.

S. Baxter PS Merry Christmas to one and all.

I’m a little perplexed because it feels like you think you are disagreeing with stuff I’ve written, but there is nothing in what you’ve written that is inconsistent with what I’ve written. An environmental economist is an economist, of course. Did I suggest otherwise? The comment that this is “a little too eclectic” is very strange. All I’m doing here is explaining the concepts presented in a set of well-known and highly influential papers by Weitzman. More theory? Come on – this is a blog post, not a journal paper.

Sir – You are defending the indefensible. A blog should not be your self-divergent theory that is possibly inconsistent with accepted economic theory. Blog or no blog. You have all these subsets of economics that would lead a student/colleague to believe they are different to general economic theory. They are not. A farm or the USSR – theory works. One cannot throw mud on the wall and hope some sticks. S.Baxter

This is one of the strangest sets of comments I have ever had on my blog. I wasn’t defending anything – I was saying there is nothing to defend. There is nothing here that is divergent from economic theory. Weitzman was one of the best economists around. Just ask his colleagues in the economics department at Harvard. Suggesting that his work was “possibly inconsistent with accepted economic theory” is completely ridiculous. His work was innovative, but entirely within mainstream economics. We don’t find out what Nobel Prize committees discuss, but I would be astonished if he was not close to winning the Prize with Nordhaus in 2018.

“By incorporating the probability distribution directly into the analysis, this paper proposes a new theoretical approach to resolving the perennial dilemma of being uncertain about what discount rate to use in cost-benefit analysis. A numerical example is constructed from the results of a survey based on the opinions of 2,160 economists. The main finding is that even if every individual believes in a constant discount rate, the wide spread of opinion on what it should be makes the effective social discount rate decline significantly over time. Implications and ramifications of this proposed “gamma-discounting” approach are discussed. ” (Weitzman) How can I take this mumbo jumbo to the local super market? What value is added to theory? Observed human behavior tells us that trade and exchange settles on market rates. Above mine? Below yours?

Everyone has a different discount rate. Discount rates change as a function of circumstances (age, education, etc.). The Scots (others) were bankers in middle-England. They had a different preference for future consumption versus current consumption than the “English.” (eat drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die). I object to your broad brush approach. You might cut down a tree long before I would. Why? Students need to know. I just do not get this in your theoretical writings. The fallacy of Bush’s rationalisation for invading Iraq being oil can challenged using theory. Saddam would have given him all the oil he wanted at discount off the market price. Only the U.S. could have toppled him at that time. QED – It was not oil driving Bush’s decision (discount rate subsumed). Bush’s political discount rate was quite different. Carry on. Please do not get too prickly in response.

Thanks for your further comments, but they are irrelevant to the topic of this post. Weitzman’s paper is about discounting in assessment of public investments with very long time frames.