229 – Past climate change and wheat yields in Western Australia

The wheat-growing areas of Western Australia experienced substantial climate change (particularly rainfall decline) during the 20th century. However, the resulting impacts on wheat yields were negligible, even after factoring out changes in technology and prices.

Western Australia is by far the largest grain-crop-producing state of Australia, and wheat is by far its main crop.

The wheatbelt underwent significant climate change during the 20th century, commencing even before climate change was a high-profile issue. The region has had a 20% rainfall decline over the past 110 years, more than any other wheat-growing region in Australia.

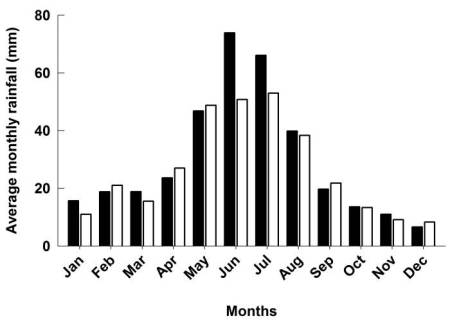

There has been a specific pattern to the rainfall decline, with most of it occurring in winter. Figure 1 shows a typical example, for the Mullewa region.

Figure 1. Average monthly rainfall for Mullewa for 1945–1974 (filled bars) and 1975–2008 (open bars)

The other important climatic variable is temperature. Average temperature in the region has increased slightly (0.8 °C) over the past 50 years, but there has been a disproportionate increase in the frequency of hot days during grain filling (Asseng et al. 2011), when wheat yields are adversely affected by high temperatures. Some of that impact may have been off-set by increases in temperature during winter, which helps to increase yields.

Ludwig et al. (2009) used crop modelling to investigate the effects of past climate change on crop yields over the past 60 years, across various locations of the Western Australian wheatbelt. Remarkably, they concluded that there has been no change in wheat yield potential. The reasons they proposed for the lack of impact of reduced rainfall are:

- Crops have low demand for water during the cool winter months in which the decline has occurred

- Given the unpredictability of weather, farmers do not apply sufficient inputs (particularly fertilizer) to achieve the higher yields that are theoretically possible in wet years, and

- Most Western Australian soils have low water-holding capacity, so a large proportion of unused water is lost below the root zone of crops.

A third change, not considered by Ludwig et al. (2009), has been the increase in atmospheric CO2. Higher CO2 has presumably contributed to the climatic changes (especially tempterature) but has another effect on crop yields, through so-called “CO2 fertilization” (Attavanich and McCarl, 2012). Increases in atmospheric CO2 concentration over the past 50 years have increased wheat yields in Western Australia by approximately 2–8 %.

Overall, I think it’s quite interesting and surprising that, despite really significant changes in climate in the region, these changes have had no significant negative impact on yields, especially when CO2 fertilization is factored in.

Overall, I think it’s quite interesting and surprising that, despite really significant changes in climate in the region, these changes have had no significant negative impact on yields, especially when CO2 fertilization is factored in.

It highlights that the specific details of the climate changes (such as their within-year timing) really matter. Changes that would be damaging at one time of the year can be benign at another. This makes it even harder to accurately predict the impacts of future climate changes, even if we get their average magnitudes right (which is already tough).

At the same time as climate change was having no impact on wheat yields in Western Australia, other things were having big positive impacts, including changes in crop varieties, increased fertiliser use, herbicides, reduced tillage, improved machinery allowing earlier sowing, retention of crop residues, and the use of ‘break’ crops that reduce root diseases. These have combined to increase average wheat yields in the region by around 100% over the past 30 years.

Some scientist have argued that farmers in this region should already be making changes to adapt to climate change. In the light of these results, that advice seems misguided.

This Pannell Discussion is based on part of a paper I’ve recently published with Senthold Asseng, who’s now at the University of Florida (Asseng and Pannell, 2012).

Further reading

Asseng, S. and Pannell, D.J. (2012). Adaptating dryland agriculture to climate change: farming implications and research and development needs in Western Australia, Climatic Change 118(2), 167-181. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-012-0623-1

Attavanich, W. and McCarl, B. (2012). The effect of climate change, CO2 fertilization, and crop production technology on crop yields and its economic implications on market outcomes and welfare distribution, Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, 2011 Annual Meeting, July 24-26, 2011, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, IDEAS page for this paper.

Ludwig, F., Milroy, S.P., Asseng, S. (2009). Impacts of recent climate change on wheat production systems in Western Australia. Climatic Change 92: 495–517.

I agree with your comment that “”I think it’s quite interesting and surprising that, despite really significant changes in climate in the region, these changes have had no significant negative impact on yields, especially when CO2 fertilization is factored in.”

A few caveats, however, are worth noting.

(i) although modelled yield differences based on recent decades’ climate point to no significant yield differences at many sites the same may not necessarily be true if greater physical changes in climate occur in coming decades. Large gains in technological improvement may be required to offset greater change in climate in coming decades (i.e. more warming, less growing season rainfall and higher CO2 concentrations)

(ii) Ludwig et al indicate that: “We analysed the impact of recent climate change on different variables by comparing two different periods: (1) 1945–1974 and (2) 1975–2004” (p. 497) This means their analysis excluded the consecutive years of decile one drought in the northern grain belts and the widespread drought in 2010. Whether inclusion of these sorts of weather-years in their “with climate change” scenario would alter their conclusion is an empirical issue. However, the more frequent poor years after 2005 suggest that it may be less valid to apply their findings to the most recent last two deacdes.

Thanks Ross. (i) I’ll comment on future climate change in the next Pannell Discussion. (ii) Fair comment. The last seven years may have been worse for agriculture climate-wise than the average for 1975-2004. It would be interesting to know how the study would look if extended for another seven years. Seven years on its own is too short a period to draw conclusions about, but expanding the study period from 60 to 67 years would be more meaningful.

I believe I read somewhere recently that the introduction of dwarf traitsin cereals may limit the beneficial impact of C02 fertilisation that may occur in other crops?

I read something like that too – that modern wheat varieties that are less responsive to elevated CO2 than are older varieties. I guess responsiveness to CO2 would not have been a consideration for plant breeders. That raises the possibility of breeding CO2 responsiveness back into future varieties.

David, you have triggered my soft spot. Although Bob Nulsen was our official “Climate Change” representative in the DOAF back in the late 80’s I took a very personal interest and stance on the issue. At that time I was quite dismissive of Graeme Pearman about his conclusion that the reduction in winter rainfall in SW WA was due to climate change. He based it on comparing rainfall records from memory between 1900 and 1985. Your article adds weight to what he said.

If in fact this is the case (and indeed the temperature change) there are aspects other than featured in your article that impact on crop yields. These are

1. Rainfall although less in an annual sense is less, it is higher in autumn (helps moisture storage and early seeding) and in September/October (helps grain filling).

2. My experience in the field between 1962- 1991 certainly indicated that flooding in June-July was a major factor in yield reduction.

3. If indeed there is a temperature change (in my day it was predicted to be 5 degrees at Albany) as well as a rainfall drop, clearly the cereal belt will move further South. This means you could grow wheat at Albany now that would have been a disaster 30 years ago unless you planted in September and accepted low yields.

4. Irrespective of the above, temperature becomes an interesting issue. Even a 1 degree increase in temperature in our north makes a significant increase in the potential for tropical cyclones and their incidence further south than they currently occur. These lower cyclones invariably pass through the fringes of our existing wheat belt. The moisture storage provided by these in Autumn would be invaluable for crops in places like Southern Cross and Salmon Gums.

5. I know your article focused on wheat but there may be better gains from other crops under a climate change scenario (eg maize at Geraldton)

Cheers

Ron

David – I assume that the comparisons of yields by Ludwig et al is a comparison by shires or zones, since the wheat growing area has been expanding to the SW as the climate has changed. So state-wide yields would be misleading. Given the collapsing chipwood industry in the SW, partly due to the Japanese Tsunami, there would appear to be increasing opportunities for growinhg wheat (and Ron’s other crops) closer to the South Coast.

They looked at nine specific sites. “Nine sites were selected within the central and northern parts of the WA wheatbelt. The nine sites covered both the high and low rainfall parts and the warmer and cooler parts of the region.”

I read the following with some interest: “How Has a Changing Climate Recently Affected Western Australia’s Capacity to Increase Crop Productivity and Water Use Efficiency?” http://agvivo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/Dr-David-Stephens.pdf

Thanks Roger. Yes that is an interesting presentation. The Western Australian wheatbelt had some really terrible weather years in the noughties .

David Stephens says that there was “an abrupt change to a more variable and dry climate” in the noughties. This wording seems to imply that the noughties weather is here to stay. If that is what he means, I don’t believe it is a conclusion that can be defended. The time frame since the “change” has been much too short, given how variable the system is.

Observing that farmers cut inputs significantly in the drought years, he comments that this “exposed a frailty in our cropping systems”. This seems an odd thing to say. To my mind, the conclusion to draw is more-or-less the opposite. It highlights that farmers can adapt to drought years in ways that reduce their exposure to risk. This is a good thing.

I do agree with him that, with the possibility of adverse climate change looming, now is not the time to be cutting agricultural R&D.