223 – Leadership

Strong, inspiring, visionary leadership can have a huge influence on people, pulling them together and changing their direction. But is it the only thing that can achieve that? And is it necessarily a good thing?

I participated in a very interesting discussion about leadership this week. One of the participants was a radio astronomer who had been involved in the successful bid for the Square Kilometre Array project in Western Australia – a massive undertaking. She said that a key factor in getting radio astronomers to overcome their differences and unify behind the bid was a small number of outstanding leaders in the discipline. Most people in the discussion were agricultural scientists, and they were discussing whether agricultural scientists could also get a large, visionary national project funded in Australia and what could be learnt from the SKA experience.

One of agriculturalists argued that leadership is not just important for change, it is essential — that you generally don’t see big changes occur across a large group of people where the change propagates from the bottom up. That was quite thought provoking, and at the time I couldn’t think of a counter example.

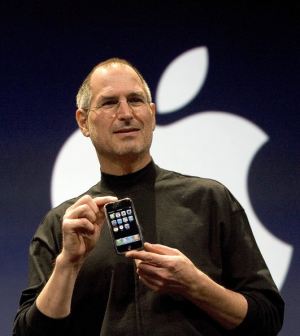

Later on I identified a couple of economics-related examples where major changes regularly happen without any leadership at all. One is our adoption of new technologies. Think of Steve Jobs and Apple. No doubt, Jobs was the archetype of a strong, inspiring, visionary leader within Apple, and had a huge influence on the company and its staff. But outside the company, it was different. We didn’t all buy ipods, iphones, ipads and ikettles because we were inspired and led by Steve Jobs. (Well, maybe a few did, but mostly not.) We did it because these are great products, and perhaps because Apple has a cool reputation. Millions of us changed our behaviour towards purchase of Apple products, and that in turn further influenced our behaviour in myriad ways, but there was no unifying leader that directly influenced us to change in these ways.

Later on I identified a couple of economics-related examples where major changes regularly happen without any leadership at all. One is our adoption of new technologies. Think of Steve Jobs and Apple. No doubt, Jobs was the archetype of a strong, inspiring, visionary leader within Apple, and had a huge influence on the company and its staff. But outside the company, it was different. We didn’t all buy ipods, iphones, ipads and ikettles because we were inspired and led by Steve Jobs. (Well, maybe a few did, but mostly not.) We did it because these are great products, and perhaps because Apple has a cool reputation. Millions of us changed our behaviour towards purchase of Apple products, and that in turn further influenced our behaviour in myriad ways, but there was no unifying leader that directly influenced us to change in these ways.

Another example is the behaviour of people in markets. Markets can have a major influence on the behaviour of people by the simple mechanism of pricing. If there is a shortage of a product (say, wheat), the price is bid up. This encourages more producers to produce wheat, and it encourages consumers of wheat to cut back on their wheat consumption, so the shortage is addressed. The wonder of the market is that there is no leadership required for this to happen. It occurs efficiently and reliably through the aggregation of many individual decisions.

Could these examples provide a different way (other than by leadership) to bring agricultural scientists together, to push them in a particular new direction? Perhaps it would be possible to think about the incentives that scientists face and influence their behaviour by modifying those incentives. That might mean that we wouldn’t need inspiring leadership, but I think we would still require strong leadership with a clear vision to arrange for the new incentives to be put in place. So for this particular type of change, my feeling is that the comment was right; leadership is crucial.

My other thought about this, though, is that we should be careful what we wish for. The directions that leaders take us in are not necessarily good ones. In the agricultural context, I’d point to the history of salinity in Australia. The profile of salinity as a problem for agriculture (as well as for water, biodiversity and infrastructure) grew through the 1980s and 1990s, culminating in the creation of the National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality in 2000. A small number of high-profile scientist leaders/advocates were pivotal in the creation of this $1.4 billion program. It was the one of the biggest environmental programs in Australia’s history, and its creation must have seemed like a huge success for those who had been pushing for it. But in fact the program was fundamentally misconceived. It would have needed to be designed and delivered in entirely different ways to have any chance of meeting its objectives. In the wake of its obvious failure, resources for salinity management and salinity research have almost completely dried up. So the apparent major success of getting a huge national program established was actually the beginning of the end of the issue as a national priority.

Further reading

Hermalin, B.E. (1998). Toward an Economic Theory of Leadership: Leading by Example, American Economic Review 88(5), 1188-1206. IDEAS page for this paper

Pannell, D.J. and Roberts, A.M. (2010). The National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality: A retrospective assessment, Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 54(4): 437-456. Journal web site here ♦ IDEAS page for this paper

Very good argument David – The market is a good leader most of the time, though you would not have wanted to buy a house in Eire in 2007.

Your article made me think of truffles at Manjimup, where Nick Malaczjuk did a lot of pioneering work, or Kevin Cullen and John Gladstones with SW wines, but both acted as their own, with little money and did not need leadership. It is in the collection of a large sum of money that requires leadership/salesmanship and that may lead to either good or wasteful outcomes, both in research and industry.

The name “Camballin” has just appeared in my sub-conscious. Several stories come from that.

Very insightful. I think leadership is more complex than we realise and that their are flaws is relying on charisma or single persons as leaders. History has a lot of examples of flaws in single leaders. A sociologist called Weber has written a lot about authority and power that can apply in this and many other contexts. The concept of group leadership, as in the Australian radio astronomers example, is interesting. It seems to me that for such leadership to be effective, it is essential to have a commonality of understanding the science (what is known, what isn’t known and why this knowledge is important), the policy context (how to bring about change) and the capacity to make this understanding clear to a wider diverse community of scientists, investors and policy makers at national and global levels is of great advantage.

In my experience of community development, a combination of working together co-operatively, sharing ideas openly and not being overly governed by competition, is what assists group leadership to make decisions and successfully implement actions. Though there is also an element of serendipity to this process.

However, I am not sure that the mantra about the market leading the way in price setting is as simple as suggested by appearances. Certainly the examples of wheat are very real but these are facilitated by belief systems and institutionalised economic structures that support and facilitate this process of price fluctuation. In our homes, we are bombarded with letters, with emails and even with telephone calls, plus radio and television messages that extort us to buy whatever. Often these exhortations are based on the best for the cheapest, but rarely are these qualities articulated specifically. In fact I think that much of the market is driven by excessive production, that in turn drives excessive consumption, which becomes cyclical. This is a useful way to share essential items around for those who have ready access to the monetary economy. Wheat is a good example because it is a staple food …. well here in Australia. But that high production of wheat is at least as much producer driven as consumer driven, it seems to me. Much of the world eats lentils, which keep longer and are more easily transported and stored, yet do not seem to generate the same market power. I doubt that this is consumer driven, but I may be wrong. I enjoy that lentils do not face high demand here in Australia, as this keeps my food costs lower. Maybe this is an example of my following an economic rationalist approach to shopping. But in fact, I find it easier to cook lentils than to bake bread. And I prefer to eat lentils than wheat or bread,

In our family, one of us is highly influenced by the quality of any given purchase. Another of us is driven by price. We regularly have debates about the relationship between these two, because the person driven by price, in our family, does not accept that a higher price automatically indicates better quality or a lower price lower quality. While the person driven by quality, is firmly convinced that the cheaper a product, the lower the quality.

Thank you for these Pannell Discussions. they provide a lot of food for thought and discussion in our family.

Thanks Saide. Yes, of course, markets require supporting institutions (like the rule of law, property rights, information networks) to operate. But it’s still the case that, with those things in place, people in aggregate respond to price. The evidence for this is so overwhelming in all sorts of contexts that there is really no need to question it. Yes, there can often be a trade-off between price and quality, or alternatively you can think of similar goods of different qualities as being different goods in competition with each other, and people making trade-offs between them.

Markets are a mix of supply and demand – you can’t have a market without both. People have to want stuff enough to be willing to pay for it, and it has to be cheap enough to produce to be provided at less than what people are willing to pay for it.

Interesting piece. Many in leadership positions often engage in routine management rather than true leadership. Leadership is more elusive as, in the case of Jobs, requires finding new solutions to problems that transform an organization. He created an environment where people were able to do this. This is often the challenge for organizations like Universities where we continue to do things because we always have and then discover too late that the world around us has changed.

Great article. In conservation, there are many examples where good leadership has been the difference between species recovery and species extinction. In an example close to home, the recent extinction of the Christmas Island Pipistrelle (small insect eating bat endemic to Christmas Island) is in part due to the lack of leadership to ensure the species’ plight and the required actions to save it were on the political agenda. In contrast, the ongoing recovery of the Orange-bellied Parrot, is a result of solid leadership in the form of a multi-agency recovery team. Leadership can come in many forms from a single empowered individual to a group of individuals or agencies with a shared vision and determination.

For more on the role of leadership in conservation, see our recent paper:

Martin, T.G., Nally, S., Burbidge, A., Arnall, S., Garnett, S.T., Hayward, M.W., Lumsden, L., Menkhorst, P., McDonald-Madden, E., Possingham, H.P., 2012. Acting fast helps avoids extinction. Conservation Letters 5, 274-280.

As always David, interesting. I am an observer and student of leadership in agricultural industries and our future. It seems to me you have brought up a degree of leadership challenges, whether it be the market, the vision for a large scale project, or thought leadership about where we are going and how we might get there. Recently I read Charles Massey’s book ‘Breaking the Sheep’s Back’. It outlines the worst of leadership, where the rhetoric became the truth, …..scary. I think collaborative leadership, such as we have seen in CRC structures is a very different model, how we take that forward in the world of doing more with less is a challenge. I like Saide’s opening comment, an outdated model of authoritarian leadership, it doesn’t attract younger people, like my gen Y children.I use communicating climate change as my leadership challenge, and make progress especially with younger farmers.

Hi Lucinda. Many thanks for reminding me about the 1990s wool crisis (which is the subject of Massey’s book). That was an even more extreme example of terrible leadership than the salinity one. A small group of wool-industry leaders brought the industry to its knees through a series of staggering bad decisions. It was totally self-inflicted and easily avoidable.

Hi Professor David, I find your article interesting and insightfull. I guess leadership can be good and bad too.. Taking the case of Singapore, A visionary leader like Lee Kuan yew turn Singapore into developed country and another leader lik Polpot of Khmer Rouge, Cambodia turn Cambodia into poverty..