216 – Diminishing marginal benefits of economics

One of the foundational concepts of economics is the idea of diminishing marginal benefits. In this post I argue that it applies to economics itself.

A classic example of diminishing marginal benefits is the application of fertilizer to a wheat crop. As you add more fertilizer, the wheat yield increases, but it does so at a diminishing rate. The yield curve gets flatter and flatter as the fertilizer rate increases.

This flattening off of benefits has been found to be extremely common as the level of an input to a production process increases (even those related to the environment – see PD183). In economic text books, it is assumed to be the default case. It underpins almost all of the field of production economics. It is built into the thinking of economists about anything to do with production.

Ironically, however, we possibly don’t often stop to think that it applies to our own discipline. If the X axis of the graph represents the level of resources and effort put into analysing an economic decision problem, and the Y axis represents the benefits generated from the resulting decision, we would expect to see just the same sort of shape to the graph.

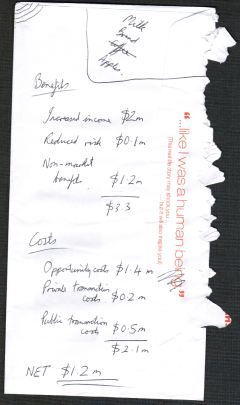

To illustrate, imagine that we have a limited budget to spend on new projects and we are trying to select from a list of potential projects the ones that will deliver the best value for money – the greatest benefits per dollar of costs.

One option for us would be to choose to do no economic analysis at all and just use our judgement about which projects are best. The projects we chose would generate some benefits. The benefits may or may not be sufficient to outweigh the costs and, unless we are freakishly lucky or clever, the benefits would be less than we could make if we did do some economic analysis.

Next, suppose we do a simple ‘quick-and-dirty’ economic analysis of each of the potential projects and calculate a benefit: cost ratio for each. The analysis wouldn’t be very sophisticated, and the numbers we used would be somewhat uncertain (because we would not be devoting much effort to getting the best possible numbers) but, nevertheless, decision theory shows that the information produced will probably help us make significantly better decisions.

You can see where this is going. There are many ways that we could add accuracy, detail and sophistication to the analysis we do of each project. For example, we could:

- explicitly represent the risks and uncertainties involved

- represent the risk attitudes of the decision makers

- represent the benefits and costs over a series of years, rather than a single year

- include ‘option values’ representing the value of deferring a decision

- conduct sophisticated statistical analysis to estimate the relationships and parameters to include in the analysis

- if relevant, conduct non-market valuation studies to estimate the intangible values expected to result from the projects

and so on.

The more sophisticated, detailed and comprehensive we make the analysis, the greater would be the expected benefits from the resulting decisions, but evidence shows that the benefits increase at a diminishing rate.

One reason is that more sophisticated modelling and better data is expensive. We can do our quick-and-dirty modelling at very low cost and get some benefits, but doing a better analysis is likely to involve a lot more effort and cost. Thus, even if we are able to double the benefits, we would probably more than double the costs, resulting in some flattening out of the curve.

Another reason is that perfect decision making imposes an upper bound on how many benefits we can generate from the decision. Once our analysis is sophisticated enough to support good decision making, the additional benefits that can be delivered through better decision making are limited to the difference between good and perfect decision making. Usually, the level of sophistication required to get to reasonably good decision making is a long way short of the frontiers of economics research.

So, where should applied economists aiming to support real decision makers strike the balance between simplicity and sophistication? There is no easy answer to that. It depends on the importance of the decision problem, the quality of existing information that their analysis will be built on, the time frame for the decision, and so on. But the existence of diminishing marginal benefits from economics means that the optimal balance will be pushed to some degree towards the simple end of the spectrum, more so, no doubt, than people who like building complex economic models would prefer!

So, where should applied economists aiming to support real decision makers strike the balance between simplicity and sophistication? There is no easy answer to that. It depends on the importance of the decision problem, the quality of existing information that their analysis will be built on, the time frame for the decision, and so on. But the existence of diminishing marginal benefits from economics means that the optimal balance will be pushed to some degree towards the simple end of the spectrum, more so, no doubt, than people who like building complex economic models would prefer!

Just to be clear, I am not arguing that any simplistic analysis is good enough. In the field I work in, environmental economics, I am constantly seeing decisions for which the supporting analysis is clearly not nearly sufficient (Pannell and Roberts 2010). But improving the quality and sophistication of the analysis doesn’t mean that we have to go to the other extreme. I believe that the analysis needs to consider all of the key factors explicitly (PD159), and to do so in a logical and theoretically sound way (PD158), but the treatment of each of those key factors can be relatively simple.

This difficult balance is something we’ve considered carefully in our development of the Investment Framework for Environmental Resources (INFFER) (Pannell et al. 2012).

Further reading

Pannell, D.J. and Roberts, A.M. (2010). The National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality: A retrospective assessment, Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics54(4): 437-456. Journal web site here ♦ IDEAS page for this paper

Pannell, D.J., Roberts, A.M., Park, G., Alexander, J., Curatolo, A. and Marsh, S. (2012). Integrated assessment of public investment in land-use change to protect environmental assets in Australia, Land Use Policy 29(2): 377-387. Journal web site ♦ IDEAS page for this paper

Hi David,

There seems to be analogies here to determining the appropriate level of detail in a statistical analysis or any model. A more complicated model is usually only supported when there are lots of data (or other source of information). That is something discussed at this blog:

http://theartofmodelling.wordpress.com

Cheers,

Mick

Yes, this concept is very broadly applicable to any type of information, not just economics.

There’s also a problem of infinite regress. Suppose we do a benefit-cost analysis to work out the optimal amount of economics to use. How precise should we be about this? Well, it’s a matter of weighing costs of effort against benefits of precision …

That’s true. There is potentially a recursive chain of decisions to make: how should I analyse this decision of whether to do an analysis for another decision? At some point we make a subjective judgment and then ignore decisions further down the chain. Going further and further down the chain of decisions (by doing analysis of each decision) would be a great example of diminishing marginal benefits.

Hi David,

It all boils down to the value of information, particularly when the decisions are subject to uncertainty. If we could relate our effort to a new activity, rather than aggregating all our effort within one production activity, certainly we could start at the IRS phase. We need to diversify into new ventures. For our profession it is a challenge.

Cheers

Thilak

Dave:

I think this was a great column. One of the things I learned when I was a Senate intern a couple decades ago is that in the political process many important decisions are made very quickly. There is no time to do research that might take two years (or even two months) to do. The time constraint you mention is thus critical. One of the problems though, is that to publish in an established area only the sophisticated analyses are typically valued. There is thus a disconnect between what we are trained to do, and rewarded for, and what might have the highest value (net benefits) to society.

Laura

Hi Laura – I think you’re absolutely right. There is often a big gap between what we are rewarded for as academic economists and what would actually be useful to people in the community. The most useful economic analyses I’ve done (in terms of making a difference to real decisions) have been extremely simple. We developed INFFER (www.inffer.org) as a tool to undertake the simplest possible economic analysis of environmental projects, but even with all those simplifications, some users still think it’s too complex. The approaches they are used to using are MUCH simpler again, and often not much better than random, but they are quick and cheap!!

This is an interesting and tilemy article as we at the Goulburn Borken Catchment Mangement Authority recognise that extension capabilitites have changed, and we need to create effective and new extension activities. We are beginning to put a project brief together where we ask farmers about their drivers and why/why not uptake environmental activitities. We aim to ask fundamental questions that you propose such as Are the practices we wish to promote actually adoptable by farmers? This project will incorporate real two way extension approach. The objective would be to inform us about how to talk to farmers, and to change extension into practice change. The project would greatly benefit from having input by researchers the CMA offers a real way to be the communication conduit between researchers and farmers, as we continuously interact with them in various ways. Personally, having completed at PhD, i understand the need for good science to underpin what we do in NRM. Is there an opportunity to discuss our project further with you/your team?

I’ve been thinking about these issues a lot lately, and perhaps at least for the ecology side of environmental decision making there is this conception that while we can potentially do analyses with lower quality data, the resulting higher uncertainty is difficult to communicate.

Is this perhaps due to the inherent “noise” in ecology being larger than in economics? Why do economists seem to be able to state things with so much more conviction than ecologists? Or are these just self perpetuating perceptions?

Cheers,

Liz

There’s a lot in your comment. I think it’s actually not too hard to communicate uncertainty simply to a policy audience. The problem is that they don’t like it! They prefer policy to be simple and certain. Or perhaps I should say that they prefer to pretend that policy is simple and certain, because they actually know that, in reality, it is almost always complex and uncertain.

In environmental economics, the ecological noise is a subset of the economic noise, so by definition the economic noise is greater. Even in other areas of economics, the noise is substantial. Don’t forget that in economics we’re talking about things like human values, human behaviour and technology change, each of which can be highly uncertain.

One important difference is that economists often approach issues from a decision-making perspective. One can have a lot of confidence in recommending a particular decision, or ruling out particular decisions, even if some of the information feeding into the decision is highly uncertain. We can explore how decisions are affected by ecological uncertainty, and if the best decision doesn’t change, your confidence increases. Thus it might be quite realistic and reasonable for an ecologist to be uncertain and unconvincing on a certain issue, while an economist looking at the same issue (and accurately accounting for the ecologist’s uncertainty) was quite confident about how best to respond.

My own strategy is to make uncertainties explicit, but to express them simply, and present them in a decision-making context, where it is apparent whether the uncertainties matter.

Thanks David, that certainly makes it clearer!