178 – Betting on wheat prices

The ‘real’ price of food (the price with inflation factored out) has fallen through much of recent history. Back in 1995, there was a view around that agricultural commodity prices had reached a turning point and were going to stay high and rise further. I tried to have a bet with a grain price forecaster that real prices would not rise, but he refused. Would I have won?

In 1995, we were doing some modelling of future agricultural production trends based on forecast prices over the following 10 years. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) had recently published a forecast that grain prices were set to turn the corner and rise in real terms over the coming decade.

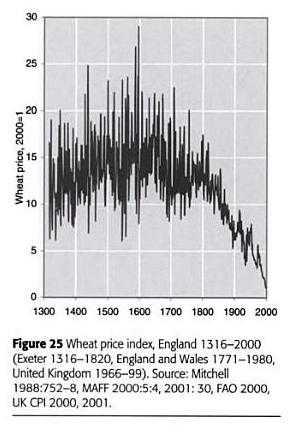

Given what had occurred historically, this was a pretty remarkable prediction. For example, the figure below shows the history of real wheat prices in England since 1300 — they’ve been falling steadily for 200 years.

The wheat price forecaster at the Western Australian Department of Agriculture was persuaded by the IFPRI analysis, and was providing us with bullish predictions to use in our modelling. I was very sceptical, and offered to bet him $100 that “The real price of wheat will be lower on December the 1st 2005 than it was on December the 1st 1995”. The price was to be for US winter wheat, using the Australian CPI as a deflator.

This proposed bet was actually favourable to him, since his forecast was for real prices to be quite a bit higher in 2005. If he believed his own prediction, the bet was far from being a 50:50 proposition. When he hesitated, I made the terms even more favourable to him by offering that the the payoff would be the price of one tonne of wheat in December 2005. If he won, the payoff would be higher than if I won, potentially much higher.

I got a good feel for how confident he was in his predictions when he refused to take even this highly skewed bet. I was pretty frustrated, especially since we had to keep using his price forecasts in the modelling! (It wasn’t our choice — our client, the Department of Agriculture, specified the numbers to use.)

So, if we had had the bet, would I have won? Yes, easily. The real price in December 2005 was only 62% of the price in December 1995.

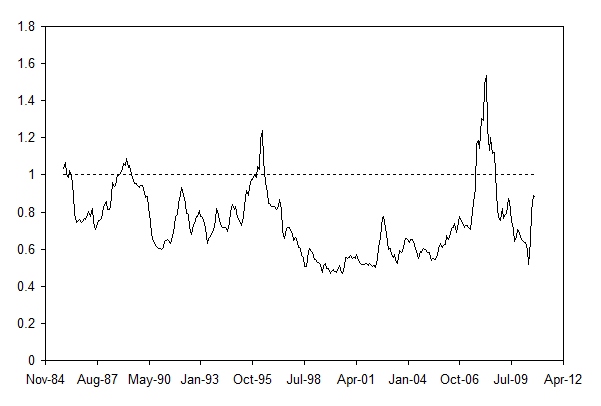

If I had specified a different time span for the bet, would I have won? Almost certainly. Figure 2 shows that only for a brief period in early 1996 and for 12 months over 2007-08 (the “global food crisis”) have subsequent real prices exceeded those in December 1995. I would have been really unlucky to lose, and if I had lost it certainly would not have been because food prices had reached a turning point and risen steadily. It would have just been the coincidental timing of a spike in prices.

Figure 2. US wheat prices relative to the price in December 1995 (both prices deflated using Australian CPI as deflator). If the line is above 1.0, it means that wheat price at that time is higher than in December 1995.

In December 1995 I had a big advantage; I knew that prices were at a high compared to recent history, so there was a good chance that future prices would be lower, maybe even if the trend line was actually upwards. What if I had made the same bet (over 10 years) starting at different points in time?

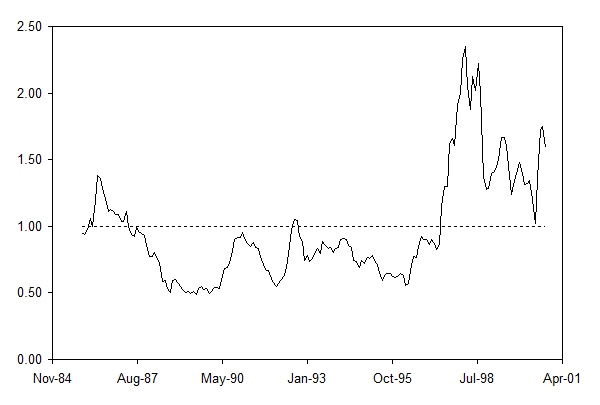

Figure 3 shows the ratio of real wheat price 10 years later to contemporary wheat price. At times when this ratio is below 1.0, I would have won the bet. It turns out that, even without the advantage of starting from a high price, I would have won almost 70% of the time for this period. The impact of the 2007-08 price spike is obvious in the results for 1997-98, but the ratio stays above 1.0 after that, not because prices were high in 2009-10 (they weren’t), but because prices plummeted after mid 1996 and were very low from 1997 to 2002. So much for steadily rising prices!

Figure 3. US wheat price 10 years later relative to current US wheat price. For example, the number for August 1987 shows the wheat price in August 1997 divided by the wheat price in August 1987 (both deflated using the Australian CPI). If the value on the graph is greater than 1.0 it means that wheat price was lower at that time than it was 10 years later.

A key lesson from this is not to get carried away by high commodity prices. In 2007, just like in 1995, people started predicting that it was the start of an era of continuing high food prices. However, economics says that the best cure for high prices is high prices. People respond to high prices in all sorts of helpful ways so that an acute mismatch of supply and demand is rapidly overcome, and prices fall. Even if people don’t understand economics, they too easily forget history, which says exactly the same thing.

Would I propose the same bet again? During a price spike, absolutely! Otherwise, probably not. Given that the world seems to be under-investing in agricultural research, and that China and India are developing rapidly, I would not expect a falling trend for real grain prices over the next decade.

One way it might fall is if governments in major countries reform their biofuel policies. Currently these are contributing to higher food prices by increasing the demand for certain grains. In some cases they are reducing supply by diverting land from food production to non-grain biofuel feedstocks. They are controversial and very inefficient policies in terms of mitigating climate change, so perhaps governments will decide to abandon them at some point.

David Pannell, The University of Western Australia

Another thing to add about grain prices going forward is that most grain is traded in US dollars. With inflation in the US flat-lining in recent years and the US devaluing its currency (e.g. ‘quantitative easing’) then many grain buyers will be able to pay more in US dollars for the corn, soybeans and wheat exported by the US. So currency devaluation will help keep the price high (at least in US dollars). However, it’s a pity about the farm-gate price for Aussie farmers whose currency has appreciated so much against the US dollar. – Ross Kingwell

Hello David, thanks for sharing your experience in this blog but I have a question about how devaluated currency makes commodities more expensive for the import party?. I Still have a doubt because as I believe, when you have a devaluated currency, then your exports are more competitive (cheaper) for buyers in international markets, so, and according to your post, my point of view would be wrong. Could you please explain me how it really works a commodity price with devaluated currency for export and import countries. Thanks

Suppose there are two countries, A and B with currencies A$ and B$. Initially, the exchange rate is A$1 = B$1.

A buys wheat from B at a price of B$200 per tonne. This costs A A$200.

Then A$ is devalued, so that the exchange rate now is A$1 = B$0.5.

After that, they still have to pay B$200 for a tonne of wheat, but to do so costs them A$400.

Came here from Coursera. Great answer, great course!

I appreciate this course and all your insight. This has been one of the best courses I’ve done so far on Coursera. Keep up the good work.

Understandable illustration

This is absolutely true. I agree with this fact because it has proven to be true over time.

i really wonder about biofuel! biofuel is very important,however food for starving population is most important.is there no way we can have them simulteneously without hamper one as matter of fact that, producing alot of food needs

high energy input

I’ve been concerned for many years about the amount of good agricultural land that is increasingly being used for biofuels rather than food. This really does need to stop. Will electric vehicles help to see the end of it?

That is where economics come in( the equilibrium)… Also a hungry man is an angry man. Better feed them first.

So the WA Dept of Ag wanted you to use optimistic projections of wheat prices, which presumably would lead to optimistic outlooks for the wheat industry, using numbers that their own expert had little faith in. What does that say about politics and ag economics?

David Salt

Dear David,

I will perfer your analysis on the effect of devaluation of currecies as against the US dollar. taking the import of wheat used in the flour & bakery industry in Nigeria. The devaluation of Nigerian currency has increasd the price of wheat, despite the lower wheat price trends globally.

We spend more in 2016 to purchase same quantity of wheat purchased in 2015.

In future, I would like the price trends of wheat to be discussed on basis of wheat producing countries and wheat importing counries, this will give us the students to compare prices in this two different cases

I hope you do some commodity trading, David?

It is amazing that the US Dollar stays strong in spite of the devaluation or all the money printing?

I don’t.

Thanks for this!

In the case of developing economies, the devaluation of a developed economy has high effect on prices of goods in developing economies since developing economies depend a lot on finished product imports from developed economies.

In the example you provided about the two countries A and B, is it the same case in this instance??

Thanks

this post seems to be very interesting and its looks like the price of the wheat is very high and will keep on rising in the upcoming years and it feels like as if we need to bet really high price to get the wheat.

The whole post is very good and give detailed information about the prices of the wheat and how people are reacting towards the situation.

Hi David,

This recent years, I personally feel, there are getting more and more skills, knowledge and technologies getting out to fast farming and fast growing of food… Would this be one of the key that cause the further fall of the next 10 years?

Substantial increases in food production (faster than rising demand) could indeed cause falls in prices.

Great insights and they are really valuable. Thank you, Prof. David Pannell. I am your Coursera student.

Can we conclude from figure 25 that long-term success of any non-industrial farming is very unlikely with established crops?

And that unless non-industrial farmers are always ‘innovating’ with fringe crops, they will not have longterm success?

Do more perishable crops fall less steadily than wheat / standard grains?

It is certainly true that the long-term trend of falling agricultural prices has meant that farmers have had to innovate to stay in business. They have to innovate to compete with other farmers who have already innovated. If small farmers are growing food for home consumption, or for local consumption in a local market that is not connected to the world market, the need for innovation is perhaps less acute.

Recent trends suggest that real prices have not been continuing to fall recently, so it seems possible that we may have reached the end of the period when the growth in production outpaced the growth in demand. But I would not bet on that yet.

Dear David,

Indeed I too will not risk to bet for a rise in production in favor of the rise in demand. The global change in climate with it’s associated risks, is calling for a mass attitude in terms of farming practices, meaning, minimize on the acreage of land to reduce mass deforestation, reduce the high production of meat products which intern produce GH gases like methane and Nitrous oxide including Nitrogen gas by increasing the production of plant protein rich food with less production of GH gases, reduce the dependent on fossil fuel but rather increase, the use of green energy like solar and biofuel technologies.

All these attempts aimed at reducing the effect of climate change will inversely reduce the cost of production at the same time lower commodity prices yet keeping the ecosystem friendly for healthy production (cheaper innovation practices) and healthy consumption.

As I understand your post, people grow more of the crops or animals that are supposed to have high prices. And it causes the supply to increase but the demand stays the same. Naturally prices decrease. So basically food prices will not go up significantly in the future because farmers will continue produce more of the goods that promise a high price. So it’s balancing itself, isn’t it?

Here I am confused about one thing. If technology is being modernized and agricultural crops and commodities are produced more efficiently, pushing down prices, then on the other hand population is also increasing day by day, pushing up prices. Should prices not remain constant or increase?

It depends on which of the two forces is stronger. If productivity increases more rapidly than increases in demand due to population growth and rising incomes, then real prices can fall, and that is mostly what has happened in reality.

Thx Sir.

Your post is very helpfully.

Reading this through the coursera course;quite insightful and informative.

My questions are 1.Can a price spike be predicted?if so,how?

2. Which is better for the economy and farmers; Price fall/ high price?

3. Can one determine a Global equilibrium price for each commodity?,if so, how?

Thanks for your time.

1. Not far in advance. Maybe it is clear just before it happens, if you can observe a big fall in global supply, say. If people could predict a spike in advance, then the spike would not happen because suppliers would adjust their production levels up in response to the higher price.

2. Farmers would prefer high prices for the things they sell and low prices for the things they buy (inputs). The question about “the economy” is too deep and too complex to deal with here.

3. During times when the price of a commodity is reasonably stable, its price on international markets is basically an equilibrium price.

This topic is very interesting. In my opinion the price spike can be predicted especially when it comes to the farming products. The climate change will change it a lot as the warmer the weather conditions the lesser the crops to and could be the reason for the price hike. For me it’s a yes, more famine in future.

I think government can take a role in this certain situation.They can subsidies these products for remaining its price high and can strictly cheek the mismatched demand and supply.

I would not support that idea. Allowing prices to fall when there is an increase in supply or a drop in demand is a good thing because it encourages producers to reduce their production (substituting production to some other product) and consumers to increase their purchases of the product, which brings demand and supply back in line.

Also, check out https://www.pannelldiscussions.net/2014/05/266-supply-and-demand-the-wool-crisis/ for an example of what can go wrong when price supports are used.

This is enlightening.

Interesting scientific writing is rare, and yours is one! Lovelym

This is insightful. Reading from the coursera course. For developing economies like Nigeria dependent on imports, global rise or fall of wheat prices rarely reflect on local prices. Perhaps a more elaborate research taking into consideration macro and micro economic factors will help one understand this local trend.

Very interesting

thank u dear sir

It’s August 2021 now. Do you win?

Try to finish my Coursera reading task. Still digesting though.

Como explicar que os países africanos, com grandes extensão de terra, continuem dependentes da exportação e não saiam do subdesenvolvimento?

Google translate says that means “How to explain that African countries, with large areas of land, remain dependent on exports and do not leave underdevelopment?”. That’s off-topic for this post, and it’s a big and complex issue, with differences between countries. In my view, the single biggest contributing factor is very bad governments. But mixed up in the stew of causes is the legacy of colonialism, the legacy of the past influence of communism, war, corruption, and so on. Those things are all tangled up with very bad governments.

This all makes sense since the issue of climate change and environmental degradation due to agricultural activities are all taking prevalence these days. It’s becoming increasingly challenging to produce the same amount of food in the same piece of land as before. Environmental activists and several regulations springing up now mean producers need to consider other factors (impact of their activities on the environment) other than producing more food.

Though some innovative companies seem to have figured it out, producing more with less of everything ranging from inputs and space, it is generally too slow to catch up to the ever-increasing demand hence the increase in the prices of these commodities. From what I have read so far, I believe this is just one factor in the equation.

This is an interesting article. I enjoy the way that you have included a personal bet within an educational example. This helped me to understand how important it is to understand supply and demand before you try to “fix” or prevent a crisis. It is important to not just look at current prices and demand but to pay attention to spikes or abnormalities as well.

This helped me to understand how important current prices and demand but to pay attention to spikes or abnormalities as well.

David, This article reveals to me the importance of data in analysis and forecasting as well as factors to always put into consideration like prevailing oil/energy and government policies before making any decision on product pricing in other for one not to bite his /her fingers. Having known the operations of demand and supply. For such a dicey decision of such nature especially in an economy that’s power/ rely on certain product such as any forms of energy mechanism which cut across nearly all the sectors of a nation economy, a spike in the price of this product affects all the areas of the economy without no respect for one. Also the policy of the day needs to be put into consideration to know where the government interest is tailored towards, whether to export or import or encourage local producers as well as to know major competitors in the global market and their production strength

Interesante, me llama mucho la atención como se mueve el mercado en este sentido y como preveer frente a escenarios y datos que ya se manejan.

Sir, if you had taken that bet in this part of the world, you might not have won because prices don’t really fall. We probably import more than we grow basically because farming is not deeply encouraged. The encouragement and support are not close to being enough and youths prefer some other jobs. When farmers are given knapsack sprayer and a bag of fertilizers each as encouragement, doesn’t that sound hilarious? The farmers spend more on all the factors of production and would not want to run loss.

I will just state that government everywhere should just regulate well, make better policies and do better to encourage farmers and to support them to prevent price hike.

Good trends for predicting prices.

For a tropical countries, production is also controlled by seasons. Some countries have two rainy seasons not winter summer in temperate climate. Other factors regulating supply of agricultural products is importation from near countries especially in Africa

Please I need a simplified explanation for figure 3 as I am having difficulties differentiating it from the explanation given for figure 2. I understand figure 2 and its explanation well enough. Figure 3, however confuses me because;

1. The graph shows US wheat prices 10 years later relative to the current US wheat prices; a. 10 years later from when to when? Are this same years the ones used for figure 2?

b. Since you did the modelling for a decade forecasting or so in 1995, does that mean the current price used against the other wheat prices was that of 2005?

2. Please, I also need an explanation for WHY and HOW?, in figure 2, below 1.0 meant the wheat prices of other years were lower than that of December, 1995 and vice versa. However, in figure 3, greater than 1.0 meant that the wheat price was lower at that time than it was 10 years later? It’s really confusing for me. I hope to receive a response, thank you.

Dear Ozioma, Sorry you found it confusing.

Figure 2 shows the wheat price at the date indicated on the X axis, divided by the wheat price in December 1995.

Figure 3 shows the wheat price 10 years after the date indicated on the X axis, divided by the wheat price at the date indicated on the X axis.

In Figure 2, values above 1 indicate that if I had bet that there would be a fall in wheat prices between December 1995 and that date, I would have lost the bet.

In Figure 3, values above 1 indicate that if I had bet that there would be a fall in wheat prices between that date and a date 10 years later, I would have lost the bet.

Cheers

David

Thank you, sir

I wish to ask how the devaluation of currencies for a producing country of wheat ‘A’ , predispose price for an importing country’B’ (the case of the example aforementioned)

Student Agricultural Economics, University of Buea.

In the example, A is not the producing country, it’s the importing country. Here’s what I said [with some extra comments in square brackets]:

Suppose there are two countries, A and B with currencies A$ and B$. Initially, the exchange rate is A$1 = B$1.

A buys wheat from B at a price of B$200 per tonne. This costs A A$200.

Then A$ is devalued, so that the exchange rate now is A$1 = B$0.5.

After that, they still have to pay B$200 for a tonne of wheat, but to do so costs them A$400. [Before the devaluation, B sold its wheat for B$200/tonne. After the devaluation, they still won’t accept less than B$200/tonne, but country A is going to pay them in A$. Since A$ are worth half as much now, they have to pay twice as many of them (A$400) to equal B$200.]