88 – Thinking like an economist 24: Flat-earth economics

Economists are often interested in finding the optimal solution to economic problems, meaning the strategy or decision that gives the highest possible payoff. In reality, in many cases, the best possible economic decision is barely any better than a large number of alternative decisions. This has big implications that economists should highlight, but which they mostly ignore.

When I was doing my degree in agricultural science in the early 1980s, while looking through the Journal of the Australian Institute of Agricultural Science for an article I needed to complete an assignment, I chanced across “One More or Less Cheer for Optimality” by Jock Anderson (1975). Intriguing title, so I read it. It was the first piece by Jock that I had read, and it was terrific. For one thing, I was very impressed that Jock could write in an entertaining and readable way in a research journal.

More importantly, I was impressed by the content, which was about the way that economic payoffs can often be quite insensitive to changes in management. For example, if you vary the rate of nitrogen fertilizer applied to a wheat crop, field measurements and some simple economic calculations show that there is usually quite a wide range of nitrogen rates that result in almost as much profit as the profit-maximising nitrogen rate. In other words, the payoff function is flat near the optimum, often over quite a wide range. In response to someone who had pointed this out in an earlier article, Jock was more-or-less saying, yes, so what?, agricultural economists have always known that. He pointed out that it is a really common phenomenon in economic models generally.

Now, I was in my honours year studying agricultural economics at the time, and I’d also done a number of units in the Economics Faculty, but nobody had ever pointed this out to me. It struck me as a hugely important observation, and a remarkable omission from my economics education.

It turned out that Jock’s paper was part of a series of comments and replies about flat payoff functions, involving a number of authors. It had been, briefly, a hot issue.

The remarkable thing – actually the astounding thing – is that, as far as I can tell, that debate in 1975 was the last time the issue of flat payoff functions was discussed in any detail in a journal. I’ve spent a long time searching, and all I’ve been able to find in the past 30 years of journal articles in economics or agricultural economics is a few brief mentions of the issue. Mostly it is completely ignored, even though it is present in most optimising economic models that are published. I’ve not seen it mentioned in any economics text book apart from a couple of specialised ones on response functions by Jock and his colleagues.

I say this is astounding because flat payoff functions are so very common, and they have such huge implications. In fact I reckon you could make a good case that the common existence of flat payoff functions is one of the most important empirical results in all of economics. And yet, all over the world, students of economics are graduating without it being highlighted, or even mentioned, to them.

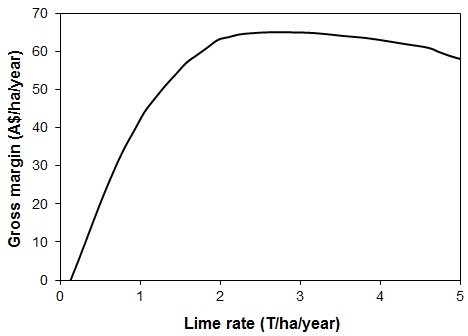

How flat is flat? Figure 1 shows one example that is not at all unusual. This is a graph of gross margin (a measure of economic payoff) as a function of lime application to crops on acidic soils in one particular situation in Western Australia (taken from O’Connell et al., 1999). The profit-maximising rate of lime in this example is 2.7 tonnes per ha, but for any rate between 1.8 and 4.3 tonnes per ha, the payoff is within 5% of the maximum!

Figure 1. Gross margin (~profit) as a function of lime rate in the Western Australian wheatbelt.

It really doesn’t matter a hoot that the optimal rate is 2.7 tonnes per ha. (It probably isn’t really, given the inevitable measurement errors, sampling errors and sheer guesswork that go into creating a graph like this.) What matters is that if you apply anything between about 2 and 4 tonnes, you’ll make about as much money as it’s possible to make from lime application. Applying 2 to 4 tonnes is vastly better than none at all, but the choice between 2, or 4, or 3.3 or 2.7 matters not one jot.

If I was applying lime, I’d want to know this. It would mean that I could consider other issues, like say risk, or liquidity, when choosing my rate. It also means that as a manager I have a margin for error, which is worth knowing since it may cost more to be precise. If I was an economist analysing this issue, I would focus on where the flat section of the curve is, and how wide it is.

By contrast, economists are commonly obsessed with finding optimal solutions. Economics journals are chock full of studies where either calculus or numerical methods have been used to find optimal solutions to economic problems. This obsession with optimisation seems to have created a huge blind spot. In 1975, Jardine noted that on presenting information to agronomists about flat profit curves for fertilizers, he “observed such reactions as complete disbelief, blank incomprehension, incipient terror, and others less readily categorized”. It would be very interesting to see how many economists today would react similarly. I’m not saying that optimisation methods should not be used, but there are implications for how they should be used.

Flat payoff functions are not important solely because of the “margin for error” issue. They also have big implications for issues as diverse as risk management, precision farming, and the value of research. I’ve written about those issues in Pannell (2006), just out in the Review of Agricultural Economics.

David Pannell, The University of Western Australia

Further Reading

Anderson, J.R. “One More or Less Cheer for Optimality.” J. Aust. Institute Agr. Sci. 41(September 1975): 195-197.

O’Connell, M., A.D. Bathgate, and N.A. Glenn. (1999). “The value of information from research to enhance testing or monitoring of soil acidity in Western Australia.” SEA Working Paper 99/06, Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Western Australia.

Pannell, D.J. (2006). Flat-earth economics: The far-reaching consequences of flat payoff functions in economic decision making, Review of Agricultural Economics 28(4), 553-566. Journal web page * Prepublication version here (44K).

Thank you very much for this information As you mentionned flat payoff usely is not consiudering In Under development country such Benin, fertilizer dose is determined for each agroecological area. The dose is the same for all year and agricultural advisor do not take into account some parameter such the rainfall deficit, the farmer financial power etc

From my comprehension, the flat payoff is very important to master to avoid frightening farmer to have not use the recommended dose of fertilizer. It is more important for farmer to ensure that the profit is enough to make sustanaible its activity and to satisfy his need, as well as improve his standard living.

Hi Eric. Yes, it is very unwise for people to focus on a specific fertilizer rate as if that is the right rate and all other rates are greatly inferior. That is definitely not the case.

“…the common existence of flat payoff functions is one of the most important empirical results in all of economics. And yet, all over the world, students of economics are graduating without it being highlighted, or even mentioned, to them.”

I agree with you on that.

This article has been one of the more informative and enjoyable ones I have read even outside of this course. Being an economist by training I too was struck by the information blackout on flat payoff functions. The author was better than simply convincing in the need for wider dissemination among economists of the “flatness phenomenon”; he opened a door of realization that optimization is not everything.

The penultimate paragraph in the article regarding the obsession with economists in finding optimal solutions is a known fact that has helped to alienate economists from more pragmatic advisory processes.

Hello, is there any metrics for measuring the environmental associated with agricultural production. for example, while we know that the cost of production to farmers can be measure in monetary value. How can the external or social cost be accounted for and then converted to monetary value, especially if it is to represented in a graph.

Thank you

Hi Cynthia. There are several Pannell Discussions about this. See numbers 218, 219, 220, 221, and 239.

Hi David, can one assume for instance that the optimal rate is the rate recommended by agriculturalists and one could work 5% either way? Can one rely on application rates printed on packaging of inputs? Or are farmers expected to calculate their own optimal fertilizer rates.

It’s fine to use the application rates recommended on packaging. The point of this article is that if a farmer has reasons to vary the rate away from the recommended rate, he/she can do so without sacrificing much income. The range over which input rates can be varied is usually much greater than 5%.

It is definitely great through this course to know this flat payoff function and the Implications, as you emphasized. However, I’d wonder if it is in a very large scale of farming operation, 2 tons to 4 tons per hectare of fertilizer in this example can make a huge difference in other perimeters, say, application costs, e.g. throughput of application either by truck or in certain other cases by air, as the rate is twice as much difference. If we factor those in, i wonder what the curve would be like – the flat payoff curve must be much narrower while shifting to the lesser rate, I guess.

At any scale it is true that as you increase inputs, the input costs go up. If you double your input rate in a field, your cost for that input in that field also double. However, that is only half the story. The other half of the story is that the benefits (the revenue from increased grain sales) go up as well. The point with flat payoff functions is that once you find the input rate that maximizes profit for a particular input in a particular field, any variation in input rate up or down from the optimal rate results in a change in benefits that is very similar to the change in costs, so they approximately cancel out. This is only true for a limited range of input levels, but that range is often quite wide.

It is well known that if you doubled the size of the Paris Metro production would not double. Why? Optimal is a word without meaning unless defined. Vague terms hide a lot on unanswered theoretical concerns.

it is useful to imcrease production

Quite insightful piece. The importance of the knowledge of the flat payoff function cannot be underestimated; as this gives farmers enough insights to consider other input factors in production, thereby limiting external and social costs.

Brilliant

Thank you very much for sharing your knowledge, professor. I have been searching for Anderson’s paper you cited in the article, but unfortunately, I cannot find it on the internet. Is there any possibility that you can share the link of the paper? Thanks a lot.

Hi Medardo, It was published in an old journal that no longer exists. You’d need to get it through a library. But if you email me, I’ll send you a copy. David.Pannell@uwa.edu.au

Would you send me that article, as well? Really enjoying your class!

It seems to me that the flat payoff function is critical, because for many crops and areas, yield estimation is far from an exact science. We don’t know with any precision, what the yield will be, but we might have a good indication from the weather forecasters about whether to expect average, favourable or unfavourable weather conditions. Based on this, we could choose to be at the low end of the flat range if we expect unfavourable weather and the high end if we expect favourable, without much risk of a major impact on profit if the weather wasn’t as [redicted.

The point with flat payoff functions is that once you find the input rate that maximizes profit for a particular input in a particular field, any variation in input rate up or down from the optimal rate results in a change in benefits that is very similar to the change in costs, so they approximately cancel out.

Being an economist by training I too was struck by the information blackout on flat payoff functions. The author was better than simply convincing in the need for wider dissemination among economists of the “flatness phenomenon”; he opened a door of realization that optimization is not everything

Another masterpiece by Dr Pannel.

The flat payoff is increasingly valuable and there is no flat or diminishing curve here.

I wish some appropriate reward/recognition shall be given to you for flagging the importance of flat payoff, or rather ignorance of it.